Zhen Shiyin's Bitter Lament

Zhen Shiyin remarks bitterly about the absurdism of life, hinting at a better way.

Zhen Shiyin's Bitter Lament

About a year ago, my wife told me about a friend of hers in Taiwan whose mother passed away due to cancer. The friend’s mother scrimped and saved her entire life, amassing a small fortune that she hoped to live off and pass along to her children. Unfortunately, her fortune wound up paying for her own cancer treatment, which proved unsuccessful in the end.

That hopeless feeling is precisely what Zhen Shiyin feels after listening to the Taoist’s mocking chant, which we covered in our last translation post. Zhen Shiyin responds in frustration, is told that the poem merely reflects the finality of everything mortal, and then responds with a deep and powerfully emotional version of the same poem.

This is the sort of section that most of us tend to skip over when we read this book — especially if we read it in translation. There’s a lot more here than you think. I’ve mentioned some of its depth in the translation notes below, but we’ll really dig into what’s going on here tomorrow.

Get ready, because this particular section can be confusing to those who are not familiar with the Chinese language. You might want to pay attention to the translation notes even if you speak no Chinese, know nothing about classical Chinese texts, and aren’t entirely sure what’s going on.

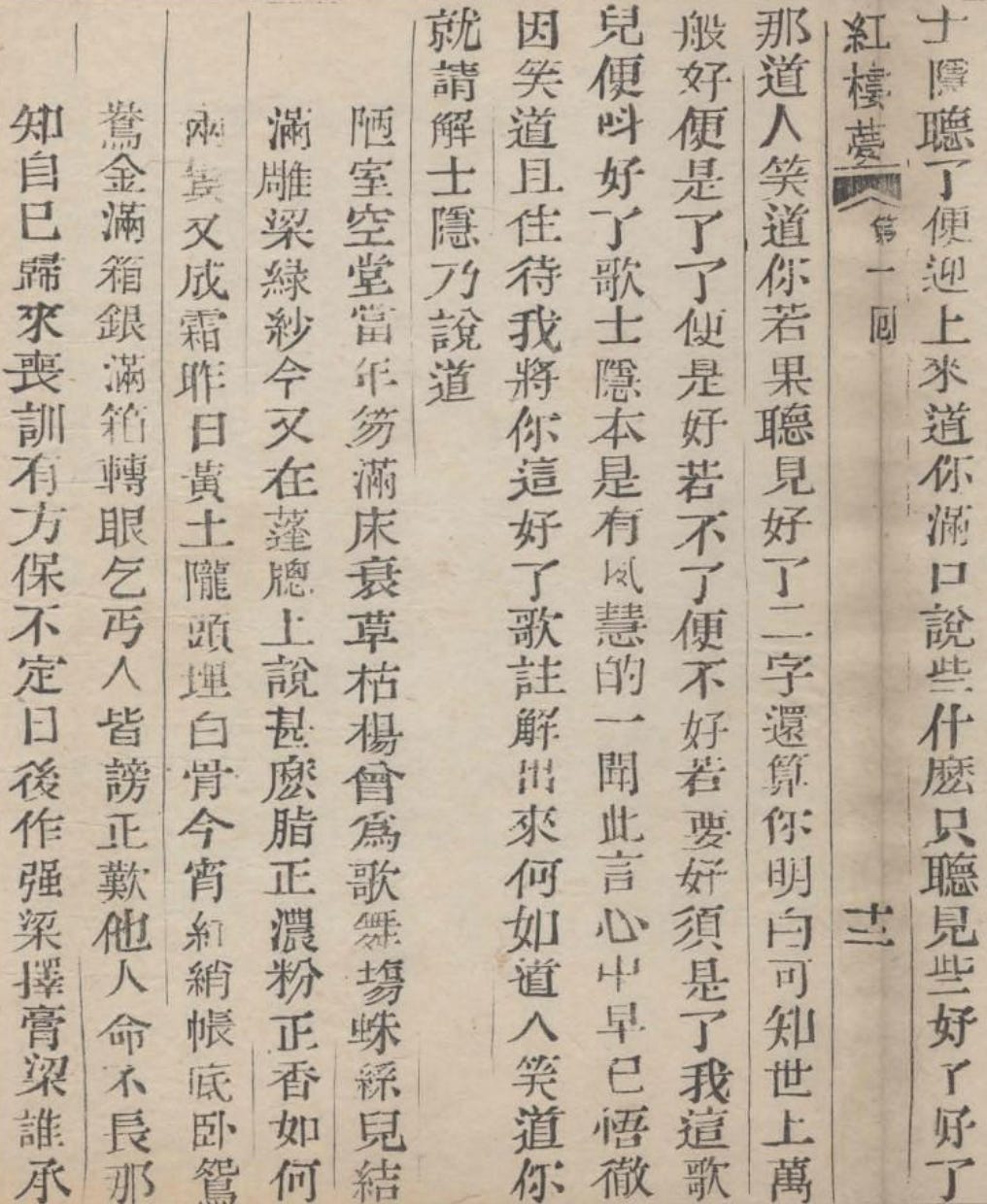

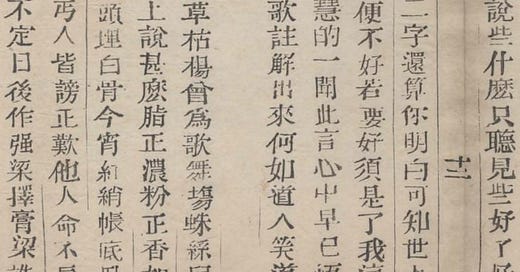

Chinese Text

士隱聽了,便迎上來道:「你滿口說些什麼?只聽見些『好了』『好了』。」那道人笑道:「你若果聽見『好了』二字,還算你明白!可知世上萬般『好』便是『了』,『了』便是『好』;若不『了』便不『好』;若要『好』,須是『了』。我這歌兒便叫《好了歌》。」

士隱本是有夙慧的,一聞此言,心中早已悟徹,因笑道:「且住!待我將你這《好了歌》注解出來,何如?」道人笑道:「你就請解。」士隱乃說道:

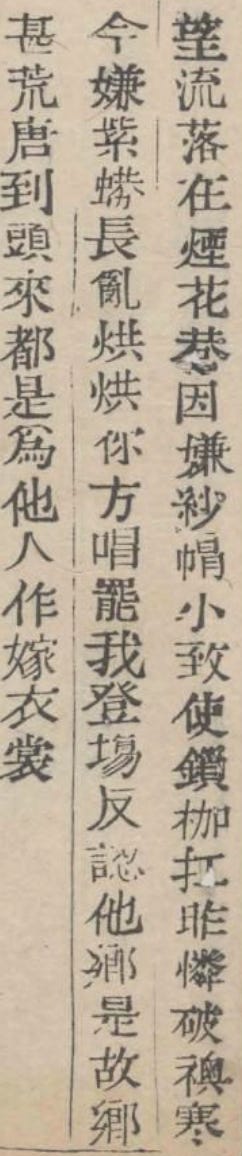

陋室空堂,當年笏滿床;衰草枯楊,曾為歌舞場。蛛絲兒結滿雕樑,綠紗今又糊在蓬窗上。說甚麼脂正濃,粉正香!如何好兩鬢又成霜?昨日黃土隴頭埋白骨,今宵紅綃帳底臥鴛鴦。金滿箱,銀滿箱,轉眼乞丐人皆謗。正嘆他人命不長,那知自己歸來喪?訓有方,保不定日後作強梁;擇膏粱,誰承望流落在煙花巷!因嫌紗帽小,致使鎖枷扛。昨憐破襖寒,今嫌紫蟒長。亂烘烘,你方唱罷我登場,反認他鄉是故鄉。甚荒唐,到頭來,都是為他人作嫁衣裳!

Translation Notes

We’re now faced with a passage that is practically impossible to render into English. The 好了歌 (The Hao-Liao song) is directly connected with Chinese grammar, and refers particularly to two characters that show up again and again in the frustrating and mocking rhyme that the priest chanted at Zhen Shiyin in our last translation post.

好, hao, means “good” and is one of the first words any Chinese student learns. 了, which should be read as liao here, can mean either “to end / to finish” (i.e. 了結, 完了) or “to understand / to clarify” (i.e. 明了, 了然). And, if you look back at the chant, you’ll see both of those characters come up at the end of the first two lines: “世人都曉神仙好,惟有功名忘不了” and so on.

Zhen Shiyin isn’t confused. He’s expressing his existential irritation at the ruthless nihilism of that poem. Because the poem keeps repeating “ 好了” over and over again, it expressed a tone of finality to fatalism. His problem with the chant is that there is simply nothing he can do, as if he were just born to lose.

When the priest keeps playing with the words 好 and 了 in his remarks (『好』便是『了』,『了』便是『好』;若不『了』便不『好』;若要『好』,須是『了』), he’s commenting on the ephemeral nature of everything in the world. Anything that is “good” will inevitably come to an “end,” and things can’t really be “good” until they actually come to an “end.” This touches on the idea of illusion (幻) that is the core of the novel. Since all things around us are illusory, according to this logic, the best way to transcend the world is to simply let go of all things that are around you and allow them to end.

In other words, the priest is basically telling Zhen Shiyin here that he should be happy that he’s completely lost his fortune and his beloved daughter. The point here, of course, is to create a feeling of discomfort in the reader, and to show the cold, unfeeling, and indifferent nature of the leading philosophies of Cao Xueqin’s day.

It applies to our day, too, as I said yesterday. It’s basically the imperial Chinese version of telling people in need to lift themselves up by their own bootstraps. Zhen Shiyin is reacting the same what that all of us should react to that kind of cold and unfeeling recommendation. He’s rejecting it.

Anyway — the cryptic nature of the Taoist’s remarks can cause you to glaze over this passage and treat it as something unimportant or silly. Don’t fall into that trap. While the Taoist’s point is made in an absurd manner, he’s basically giving the old “C’est la vie” argument: “That’s just how life is, and there’s nothing you can do about it, so you should be happy with what you’ve got.” It’s cold and heartless — and Zhen Shiyin’s careful response only makes sense when you realize just how cold and heartless the Taoist truly is.

夙慧 means to be wise far beyond one’s years, or to possess innate wisdom. Zhen Shiyin already knows and understands what the priest is telling him – but he simply cannot accept it. In a way, this means that he is beyond the cruel tool of “enlightenment” that is the 好了歌. And yet, even though Zhen Shiyin is already an ideal disciple, born with understanding, the cold words of the priest still hurt him a lot.

悟徹 is sudden enlightenment and piercing clarity. Of course, Zhen Shiyin didn’t suddenly come to some sort of meditative enlightenment. The reality of his plight hurts.

注解 means to annotate – but Zhen Shiyin isn’t just explaining the song here. He’s dissecting the cruel logic of the song.

陋室空堂 implies poverty and a theme of abandonment. The room is shabby and poor; the hall is completely empty.

笏 is a tablet used by officials at the court. 床 does not mean “bed” in this poem, but, rather, a sort of display rack or a container for ceremonial tablets (笏) used by officials. In other words, 笏滿床 gives us the image of a container filled to the brim with ceremonial tablets.

衰草 means decaying grass, and 枯楊 means dried up poplar trees – clear symbols of decline and decay.

蛛絲 is a cobweb or a spider web. 綠紗, “green gauze,” was actually a luxury item in the Qing dynasty – but, in this poem, is being used as a crude way of repairing a window. It gives the image of fallen families desperately trying to cling onto remnants of their past.

鬢 is the hair on the temple of your head. Turning to frost (成霜) refers to one’s hair turning gray.

隴 here is an alternate form of 壟, which means “grave” or “mound.” 宵 means evening, and 鴛鴦, “mandarin ducks,” is a common symbol for newlyweds. There’s a direct contrast here: the bones buried beneath the grave yesterday with the images of passionate love today. Note in particular the stark contrast between the “yellow dirt grave” (黃土隴) and the “luxurious red bedding” (紅綃帳) – yet another example of the prominence and symbolism of the color red in this book. The idea here is that your wife, who cried at your burial today, winds up married again to another man tomorrow.

訓有方 can be rough to understand. 訓 is to instruct or educate; 有方 means “having proper methods” or “using the proper system.” Note that no subject is given: this is pretty common in Chinese poetry. Here the subject of “your son” is implied because this is a parallel to the Taoist’s mocking chant. 強梁 refers to banditry. Basically, raising your son with correct Confucian principles is no guarantee that he won’t become a robber anyway.

Similarly, 擇膏粱, “select fat meat and fine grain,” implies marrying your daughter to the rich elite. The connection is implied here because of the parallel with the “訓有方” we saw above. 膏粱 means “rich family” or “extravagant person” in a figurative sense; the idea here is that you are selecting a rich family to marry your daughter off to. 煙花巷, meanwhile, refers to prostitution: 煙花, literally “smoke and flowers,” is a traditional euphemism for prostitution, and 巷 refers to the alleyways that made up the brothel districts in ancient times. Basically, marrying your daughter off to the most elite person doesn’t mean that she won’t fall into prostitution in the end.

紗帽 is the kind of black hat worn by feudal officials, and can also mean “official post” in a figurative sense. 鎖枷 is the heavy wooden collar used for prisoners in the old days. The idea here is that chasing after promotions leads to disgrace. Meanwhile, 破襖寒 literally means “shivering in rags,” and “嫌紫蟒長” means you’re upset because your purple dragon robe (a robe worn by officials) is too long. The idea here is clear: you complain that you’re not on the top enough, and, next thing you know, you’re on a chain gang. Or you’re freezing to death one day, and the next day you find yourself complaining because your beautiful clothes are too warm.

他鄉, “foreign lands,” is also a translation of the Sanskrit term संसार (saṃsāra: the mortal or “illusory” (幻) world). Similarly, 故鄉, “ancestral home,” is also a translation of the Sanskrit term निर्वाण (nirvāṇa: one’s “true home”). Today you’re up and I’m down; tomorrow I’m up and you’re down; and we falsely conclude that this is the nirvana that we’re searching for.

為他人作嫁衣裳 is a phrase from the poem 貧女 (Poor Girl) by the Tang dynasty poet 秦韜玉 (Qin Taoyu). It goes like this:

蓬門未識綺羅香,擬託良媒益自傷。

誰愛風流高格調,共憐時世儉梳妝。

敢將十指誇偏巧,不把雙眉鬬畫長。

苦恨年年壓金線,爲他人作嫁衣裳。My humble gate never knew the scent of silks and perfumes,

Yet seeking a matchmaker only deepens my wounds.

Who now admires grace and noble taste?

The world prefers frugal dressing and modesty.

I dare to boast about my nimble fingers,

But refuse to paint long eyebrows in shallow lines.

I’ve spent year after year in meticulous, exhausting labor,

Only to be sewing another woman’s bridal gown.

A note on this poem: 把雙眉鬬畫長, “compete to paint your long eyebrows in a shallow line,” is a metaphor for women who rival each other in superficial beauty standards. Also, 壓金線 refers to pressing golden thread, an act that represents meticulous and exhausting labor.

Qin Taoyu’s poem is quietly ferocious. Her refusal to “paint long eyebrows” is a quiet act of defiance, and represents the forced self-erasure of women in traditional Confucian society.

The interesting thing, of course, is that Zhen Shiyin, a man, is the one quoting these lines. This may be representative of Zhen Shiyin crossing gender roles, switching from one obsessed with form and the Confucian world around him to one with insight into suffering and pain.

Remember the words from the very beginning of the novel: “我堂堂鬚眉,誠不若彼裙釵,” or “Despite my mustache and long beard, I truly am no match for their skirts and hairpins.” Cao Xueqin is not only making a feminist argument here, but he’s literally tearing down the barriers between the genders, showing that true enlightenment means embracing the insight into suffering culturally associated with the feminine. And this is a theme that we’ll see come up again.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

Hawkes calls the 好了歌 the “Won-Done Song.” “Won” is his translation for 好 in the Taoist’s chant (each line starts with “Men all know that salvation should be won”), and “done” is his translation for 了 (each second line ends with “done,” for example “But with their loving wives they won’t have done”).

The effect of all this in English is to only make the Taoist priest’s statement more confusing.

When I first dove into the Hawkes translation years ago, this passage confused me to the point where I just skipped on through it. It’s not readily apparent from the text itself precisely why we’re spending so much time with Zhen Shiyin, after all: I wanted to see where Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu were going to come in, and was getting sick of all this cryptic talk.

The Chinese original is also confusing, as I’ve noted above. But Hawkes’ creative translation only muddies the waters more. When the priest says “in all the affairs of this world what is wone is done, and what is done is won; for whoever has not yet done has not yet won, and in order to have won, one must first have done,” he seems to be making a cryptic point that has absolutely nothing to do with Zhen Shiyin’s circumstances.

In the original, however, the finality of 了 is contrasted with things that are good (好). The priest is telling Zhen Shiyin that all things in life will vanish away anyway, so he shouldn’t be too upset about losing his child, his house, his land, and all his money.

You can’t get to that point with the Hawkes version of the “Won-Done Song,” not even if you reread it a thousand times. His translation obscures the original point in favor of making a cute poem.

Hawkes’ version of Zhen Shiyin’s reply rhymes, which is satisfying. However, its rhythmic structure lies in stark contrast to the irregular nature of the original text. It’s impressive, sure, and the translation is accurate — but it’s far too easy for the reader to just gloss through it without thinking about what Zhen Shiyin is actually saying.

Yang

The Yangs try to translate the general sense of the 好了 paradox. “You should know that all good things in this world must end,” says their priest, “and to make an end is good, for there is nothing good which does not end.”

That’s a much better approximation of the original meaning, though it doesn’t quite do the trick. It’s not just that it’s good “to make an end.” The point here is that all things will inevitably be destroyed and fade away — and so Zhen Shiyin should be happy that he lost it all.

This is kind of like Job’s Biblical cry “The Lord giveth, the Lord taketh away, blessed be the name of the Lord.” That sense doesn’t really come out in the Yangs’ version.

The Yangs also don’t do a great job with Zhen Shiyin’s poem. For example, “While yet the rogue is fresh, the powder fragrant / The hair at the temples turns hoary — for what cause?” is really vague and doesn’t get the point across. The point in the original is that there’s no reason to be happy about your youth, vigor, and beauty today when your hair is just going to turn gray tomorrow anyway.

The Yangs separate Zhen Shiyin’s poem into four stanza lines. It’s easy to read, sure, but they mismatch the stanzas, not realizing which parts actually belong together. Compare their organization with what I’ve written below.

Also — their final line, “And all our labour in the end / Is making clothes for someone else to wear,” is far too weak for 都是為他人作嫁衣裳. You’re not making “clothes;” rather, you’re making a wedding gown for someone you don’t even know.

I should note again that 為他人作嫁衣裳 is a phrase that any educated reader in 19th century China would have recognized right away. I’d argue that most educated readeres today know this phrase as well. Sadly, neither the Yangs nor Hawkes provide a footnote of explanation.

My Translation

Shiyin heard this, went up to the priest and said, “What in the world are you talking about? All I could hear is ‘hao’ and ‘liao’ over and over again.”

“If you heard ‘hao’ and ‘liao,’ then there is still hope for you!” laughed the priest. “You see, in this world all “good” (hao) things are “finished” (liao), and “finished” (liao) things are “good” (hao). Without liao there can be no hao, and to achieve hao you must first reach liao. My song is called ‘The Hao-Liao Song.’”

A man of innate wisdom, Shiyin felt these words pierce through him like cold light. “Wait!” he said, forcing a laugh. “Let me unravel this Hao-Liao Song for you – what do you think?”

“Go ahead,” replied the priest, “enlighten us.”

Zhen Shiyin replied:

This shabby room, this hollow hall —

Once piled high with nobles’ tablets.

These withered weeds, these barren poplars —

Once a stage for song and laughter.

Cobwebs now drape the carved beams,

While green gauze patches up the straw-thatched window.

Why boast of fresh rouge and fragrant powder

Now that your hair has turned to frost?

Where yesterday white bones were buried into yellow earth,

Tonight lovebirds nest beneath crimson silk drapes.

Chests overflowing with gold and silver —

yet, in a flash, you’re a beggar, mocked by all.

You sigh at the untimely end of others

Never guessing that your own coffin awaits.

You raised your son with every proper rite,

And yet he turned to banditry.

You married your daughter into luxury,

And yet she sunk deep into prostitution.

Because you crave a higher rank,

You’ll be a prisoner tomorrow.

Yesterday your were shivering in rags,

Today your expensive robe is too long.

Chaos and clamor:

As one act ends, another takes the stage.

One mistakes foreign homes for his homeland.

It’s all absurd, and, in the end,

You’re just sewing someone else’s bridal clothes.

Clear as mud, right? We’re going to dive into this poem even deeper tomorrow. So stay tuned — and please let me know what you think in the comments!

Hi Daniel,

You are putting amazing effort into this and I am grateful. My Chinese is very rusty. I have read the Hawkes translation twice and love it.

It would be even better for me if you added more pinyin to the translation notes, since I understand some Chinese but certainly not enough to read the novel. You write: "好, hao, means “good” and is one of the first words any Chinese student learns. 了, which should be read as liao here, can mean either “to end / to finish” (i.e. 了結, 完了) or “to understand / to clarify” (i.e. 明了, 了然). And, if you look back at the chant, you’ll see both of those characters come up at the end of the first two lines: “世人都曉神仙好,惟有功名忘不了” and so on."

Shìrén dōu xiǎo shénxiān hǎo, wéiyǒu gōngmíng wàng bùliǎo. OK, I got that from Google Translate and can't confirm the tones.

It takes me ages to look up all the characters. And you write that your audience do not have to be fluent Chinese readers. But just giving the characters without the pinyin seems to be intended for an audience that does not include me.

Margaret

Thanks very much for both speedy replies, Daniel. Actually I can't remember seeing ChineseConverter.com before and it solves my problem, as I can get a block of characters followed by a block of pinyin, and that helps me understand what you are referring to, e.g. when you write "通靈 could mean a number of things. ..." - I don't feel comfortable unless I can say the term to myself.

I take your point about pinyin not always being appropriate or easy. I wasn't even thinking of the poetry or that the modern Mandarin is not appropriate. I have heard of the 平 (píng) and 仄 (zè) before but how far I will get into the details of the poetry I can't tell - it might be too time-consuming.