Zhen Shiyin Loses Everything

Zhen Shiyin proceeds to lose everything: his house, his land, his livelihood, and even all of his money. He is taken advantage of by his father-in-law, and winds up encountering the Taoist priest once again, who offers words that are anything but encouraging.

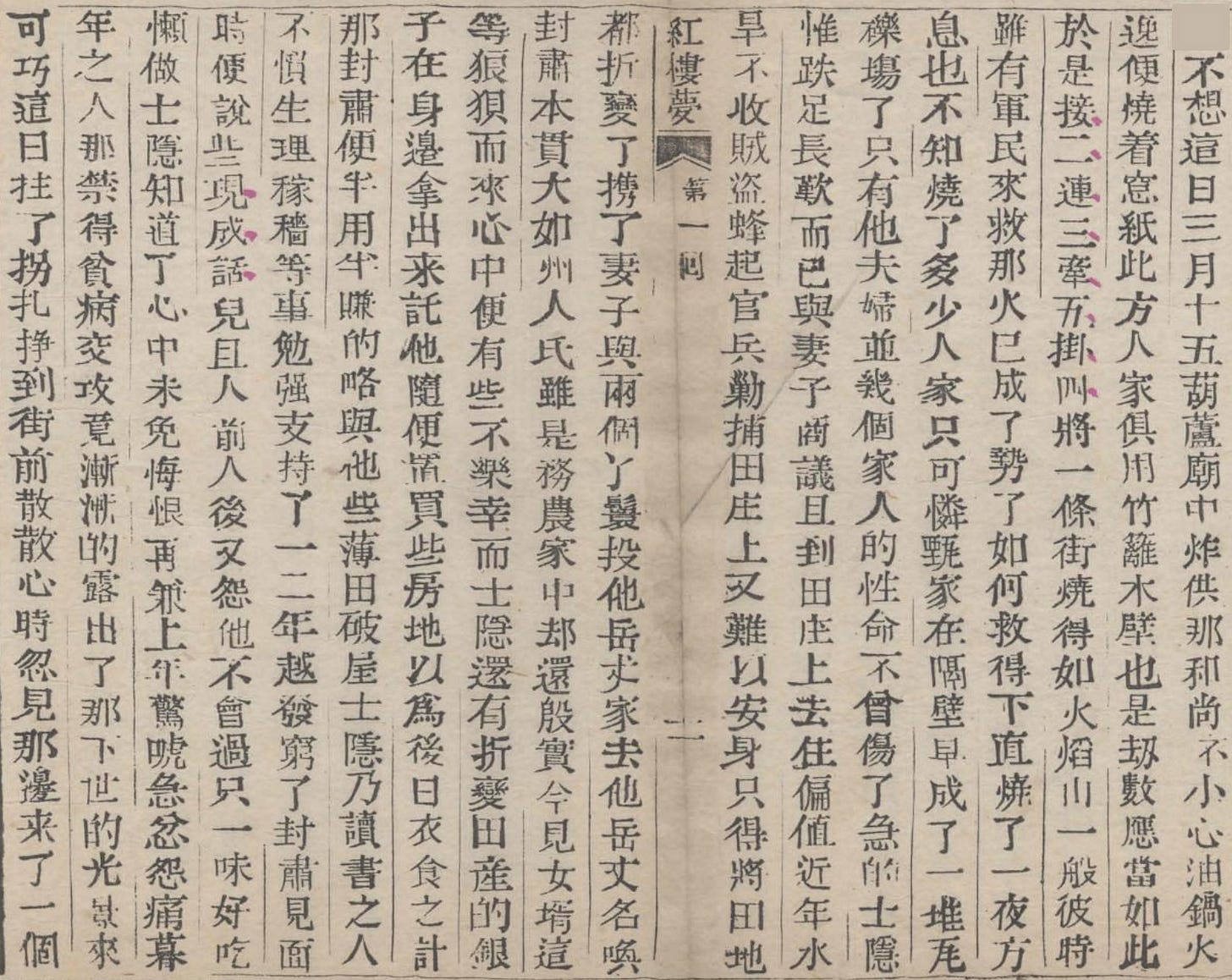

Chinese Text

不想這日,三月十五,葫蘆廟中炸供,那和尚不小心,油鍋火逸,便燒著窗紙。此方人傢俱用竹籬木壁,也是劫數應當如此,於是接二連三,牽五掛四,將一條街燒得如火焰山一般。彼時雖有軍民來救,那火已成了勢了,如何救得下!直燒了一夜方息,也不知燒了多少人家。只可憐甄家在隔壁,早成了一堆瓦礫場了,只有他夫婦並幾個家人的性命不曾傷了。急的士隱惟跌足長嘆而已。與妻子商議,且到田莊上去住。偏值近年水旱不收,盜賊蜂起,官兵剿捕,田莊上又難以安身。只得將田地都折變了,攜了妻子與兩個丫鬟投他岳丈家去。

他岳丈名喚封肅,本貫大如州人氏,雖是務農,家中卻還殷實。今見女婿這等狼狽而來,心中便有些不樂。幸而士隱還有折變田產的銀子在身邊,拿出來託他隨便置買些房地,以為後日衣食之計。那封肅便半用半賺的,略與他些薄田破屋。士隱乃讀書之人,不慣生理稼穡等事,勉強支援了一二年,越發窮了。封肅見面時便說些現成話兒,且人前人後又怨他不會過,只一味好吃懶做。士隱知道了,心中未免悔恨,再兼上年驚唬,急忿怨痛:暮年之人,那禁得貧病交攻?竟漸漸的露出那下世的光景來。可巧這日拄了拐掙扎到街前散散心時,忽見那邊來了一個跛足道人,瘋狂落拓,麻鞋鶉衣,口內念著幾句言詞道:

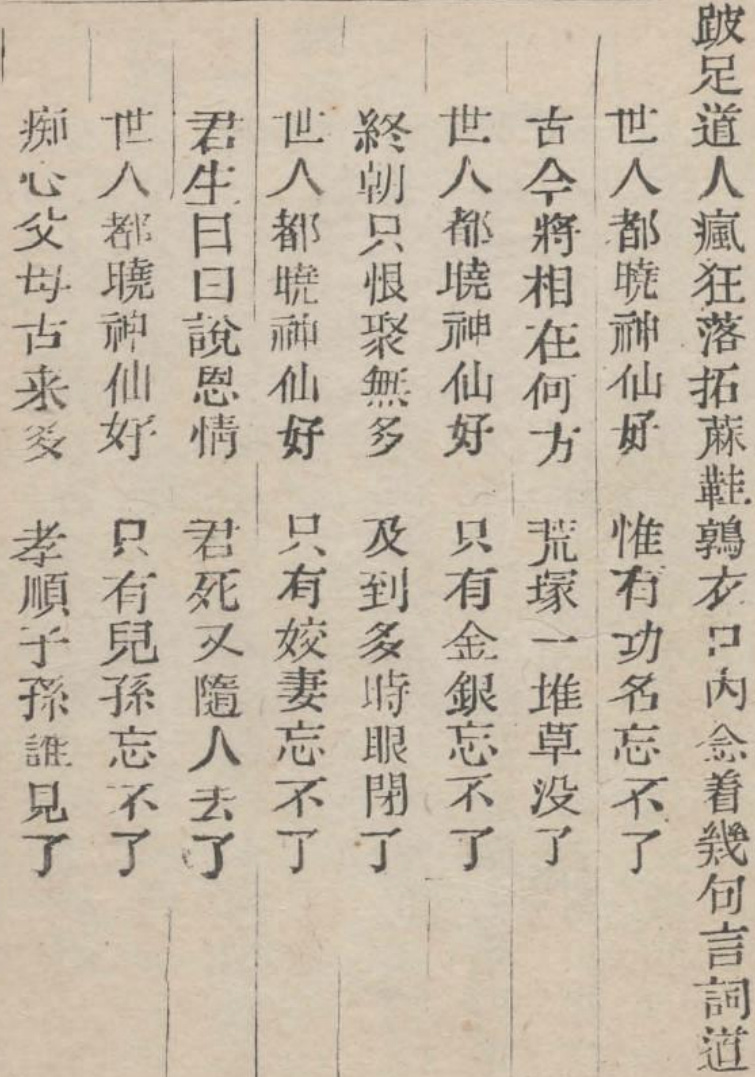

世人都曉神仙好,惟有功名忘不了。古今將相在何方?荒冢一堆草沒了!

世人都曉神仙好,只有金銀忘不了。終朝只恨聚無多,及到多時眼閉了!

世人都曉神仙好,只有姣妻忘不了。君生日日說恩情,君死又隨人去了!

世人都曉神仙好,只有兒孫忘不了。痴心父母古來多,孝順子孫誰見了!

Translation Notes

不想這日 is a rhetorical device that introduces an unexpected or coincidental event. It means something like “Little did anybody expect that on this day.”

三月十五 would have been a full moon per the lunar calendar, and would have been near the end of the Qingming Festival (which has a focus on ancestor worship and tomb sweeping). The 15th day symbolizes completion and reversal in connection with the full moon.

牽五掛四 (literally “grabbing five and hooking four”) is an unusual phrase, even when it comes to Chinese idioms. Most Chinese idiomatic phrases go upwards in number – for example, 亂七八糟 (“chaotic” – starts with the number 7 and goes to 8) and 低三下四 (“servile” – starts with the number 3 and goes to 4). By inverting this order, Cao Xueqin gives the literary impression of utter chaos.

火焰山 means Flaming Mountain, and is the name of a ridge located on Tian Shan in Xinjiang. In this context, though, it refers to a legendary Fire Mountain, a mythical, impassable, supernatural mountain in Journey to the West that impedes the journies of Sun Wukong and the monk.

跌足 means to stamp one’s foot. 跌足長嘆 (stamping one’s foot and sighing) shows the futility that Zhen Shiyin faced. Nothing he could do would make anything right.

蜂起 literally means to rise up like hornets. It’s a pretty apt description for the sudden appearance of bandits (盜賊).

剿捕 means “to surround and capture.” The countryside was a mess, with bandit groups rising and with constant official campaigns to suppress them.

折變 specifically means to sell your assets (land, in particular) at a loss. Note that selling his land means that Zhen Shiyin loses all of his social standing and his ability to earn income easily. This is the apex of his financial ruin.

丫鬟 literally means a fork-shaped bun (or a double knot) in a woman’s hair. Unmarried young women tended to use this hairstyle, which became strongly tied with servant class women during the Ming dynasty. Thus, it refers to servants and women with inferior social status.

Like so many other names we’ve encountered, 封肅 is likely a reference to a common Chinese word with the same pronunciation. In this case, it’s related to 風俗, “customs.” Note as well that 封 (“seal,” or “close off”) and 肅 (“stern,” “austere”) are both ideas that evoke a feeling of rigidity – similar to how the customs that Cao Xueqin constantly criticizes are oppressive.

大如州, “Daru Prefecture,” is almost certainly a fictional creation. There’s no evidence of a place by this name during the Ming or Qing dynasties. Cao Xueqin generally avoided using real place names due to political sensitivity.

殷實 means economically well-off. In this case, 家中卻還殷實 indicates that he was surprisingly well-off. He wasn’t necessarily rich, but he was doing pretty well given his status as a farmer.

狼狽 literally referes to a wolf and a mythical wolf-like creature, and symbolized a helpless disarray. Think of a wolf trying to carry a crippled companion. Figuratively, this means Zhen Shiyin’s disheveled and pitiable condition.

有些不樂 is a bit more than just “a little bit unhappy.” It’s more like Feng Su felt active displeasure, or even resentment, at being faced with the sudden burden. And, yes, this is a pretty petty reaction to family members who have just lost everything.

半用半賺 means “half use and half earn,” and refers to splitting the money between partial use and personal profit. Feng Su basically took the money for himself and grabbed a few poor pieces of land and run-down huts to give to Zhen Shiyin in return.

生理稼穡 is a combination of “livelihood” and “farm work.” Taken together, it probably means something like “the farming life.” Zhen Shiyin was so accustomed to the easy life of a scholar that he didn’t know much about how to actually earn a living from scratch.

現成話兒 means “ready made words,” and likely refers to empty praise that Feng Su threw around haphazardly.

人前人後 literally means in public and in private. In this case, Feng Su is complaining shamelessly about Zhen Shiyin at basically every possible opportunity.

好吃懶做 means fond of eating and lazy at doing things.

上年 must mean “recent years” rather than just “last year” based on the context in the book.

暮年 means the declining years of one’s life.

貧病交攻 literally means the dual assault of poverty and sickness.

落拓 means “unconventional.” In this sense, the priest looks wild.

鶉衣 means patched up clothing. 鶉 means “quail,” in particular a quail with spots on its feathers.

姣妻 means “beautiful wife.” 姣 is a pretty uncommon literary word meaning “beautiful.” It also came with sensual overtones, and was used to mean “lewd” or “flirtatious” in a number of Chinese dialects for years.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

Hawkes refers to the “軍民” who come to put the fire out as “firemen,” which gives an inaccurate picture to modern readers. There was no fire department in the early Qing dynasty.

Hawkes calls 現成話兒 “a few pearls of rustic wisdom,” giving the false impression that Feng Su was actually trying to help Zhen Shiyin. The truth is that Feng Su was giving him empty words of praise when needed, but was also quite openly criticizing him behind his back.

Meanwhile, Hawkes’ translation of the Taoist’s poem is quite well done, with an interesting rhyme and rhythm while matching the original text exactly.

Yang

The Yangs write that Zhen Shiyin had to “mortgage” his land before living with Feng Su. This is simply a mistranslation. It’s clear in the original that he had to sell his land at a less than desirable price.

While their translation of the Taoist’s poem is fine, there is a line in the last stanza, “yet with getting sons won’t have done,” that really doesn’t make sense. This is an unfortunate example of sacrificing the sense of the poem in favor of the form.

My Translation

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dream of the Red Chamber to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.