The Original Versions of Dream of the Red Chamber

Also - what the "celestial mystery" actually is

The Original Versions of Dream of the Red Chamber

Things are getting a little bit abstract and hard to understand. In fact, in yesterday’s post we learned about the mystical “玄機,” which means “arcane truth,” “heavenly mystery,” “celestial secret” or something similar to that. We naturally want to know what in the world the monk was talking about — but we need to take a step back first and give this all some context.

As you may or may not know, 紅樓夢 has an incredibly long and complex textual history. In fact, unlike most other classical works of fiction, the textual history itself is just as interesting and important to scholars as the actual content of the book. In fact, its textual history is so important that something like 1/4 of the brief discussion of the book in The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature is devoted to the history of the text itself.

There are all sorts of places you can go to learn about this textual history. As usual, Wikipedia is a good resource to start off with — although it can be really confusing for somebody new to the novel.

The reason why I didn’t start this project out with a long and detailed description of the textual history, or why I don’t look up alternate readings and versions of every single line of text, is because I want to avoid that confusion. So let’s take a quick look at the text that we’re using here, how it’s different from the other versions, and why we’re doing what we’re doing.

The 1792 Chengyi Version

We’re using the 1792 published version of the text (the 程乙本, or “Cheng B Version”) as our base text.

This is the version that most native readers are familiar with. This is the version of Dream of the Red Chamber that has been so influential to modern Chinese history.

Of course, if there’s a “Cheng B Version,” you’d expect there to be a “Cheng A Version” of the book. And there is. This is called the 程甲本, and was printed in 1791.

By the way — the different names of these editions don’t come from the original publishers. These were names given to the original versions by the famous scholar (and former Chinese Ambassador to the United States) Hu Shi back in the 1920s, when the field of “Redology” (or Red Chamber Studies) started to take off. In other words, if we were to go back to the 19th century and check out the Dream of the Red Chamber scene, the only version people would be familiar with would be the 1792 edition.

Now, the name 程 (Cheng) refers to one of the publishers. The story behind this edition is that two editors, Cheng Weiyuan (程偉元) and Gao E (高鶚), were fans of the original manuscripts that had spread around Beijing. You see — handwritten copies of draft versions of Cao Xueqin’s book had spread among literary circles in Beijing for decades after Cao Xueqin died in 1765.

The problem with the handwritten versions, however, is that only 80 chapters spread in anything close to a final form. Readers were upset that the book had no ending.

After a lot of searching over many years, Cheng Weiyuan and Gao E were allegedly able to come across incomplete versions of the final 40 chapters of the book. Both of them engaged in a laborous editing process.

The 1792 version includes a version of the final 40 chapters that is allegedly based on a better original manuscript than the 1791 version.

The Handwritten Versions

Scholars probably wouldn’t care much about this if it weren’t for the existence of numerous early, handwritten versions of the book.

These copies tend to be incomplete. In fact, I’m unaware of any handwritten versions from before 1791 that contain the final chapters.

The English Wikipedia page is kind of unclear on this point, and even the Chinese page doesn’t go into much detail. The truth, as I understand it, is that early manuscript editions that contain the final 40 chapters, such as the Mongolian Prince’s edition (蒙古王府本, which probably dates to the 1760s), contain 40 chapters that were clearly transcribed from the published version after 1791.

There isn’t much physical evidence that Cao Xueqin even composed the final 40 chapters.

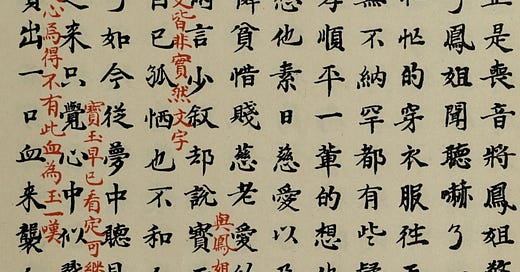

What we do have in the early versions, though, is fascinating. Certain versions contain handwritten notes from early readers, including the famous red ink commentary of 脂硯齋 (the Red Inkstone Commentary), which looks kind of like this:

I don’t know about you, but I think it’s really cool to have access to handwritten versions of a famous novel that have handwritten editorial annotations like this.

We know that the red comments were influential in how the book was put together, because we can see from the handwritten copies that Cao Xueqin took many of these comments and notes into consideration as the text developed. However, we should also note that we don’t have anything even close to a complete copy of all handwritten versions and all possible commentaries. It’s all pretty fragmentary, and it makes figuring out exactly how the text was composed kind of difficult.

Why This Matters

So who cares? Why even bother with the manuscripts?

Well, it turns out that there are a lot of people who care deeply about 紅樓夢. In fact, some of them care so deeply about it that they search and search for evidence of some sort of conspiracy theory.

Perhaps Cao Xueqin turned this book into a tragedy because of political influence, they think. Perhaps the censorship of literature in the Qing Dynasty forced him to take his true thoughts out of the book, or to deliberately obscure them. Perhaps we can prove that Gao E and Cheng Weiyuan were frauds, that they deliberately changed a great love story into a great love tragedy, and that Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu were supposed to have an eternal love connection after all.

It gets worse, of course. Contemporary versions of the book in Chinese tend to incorporate ideas and readings from the various extant handwritten copies — often without bothering to inform the reader about what they’re doing.

That’s the reason why the textual history here really matters. If you’re going to mess around with what the book actually says, you owe it to your readers at the very least to let them know somewhere that you’re messing around with stuff.

Now, the funny thing about the two English versions of Dream of the Red Chamber is that neither one of them is based on the 1792 version. The Gladys Yang version is based on a combination of commercially available copies of the novel that were sold in China in the 1960s, as well as whatever photocopies of handwritten manuscripts she and her husband could acquire during the chaos of the Cultural Revolution.

The David Hawkes edition is even worse. Hawkes made numerous editorial modifications to the original text, including combining completely different handwritten versions and occasionally taking away sections of the text that he simply didn’t like.

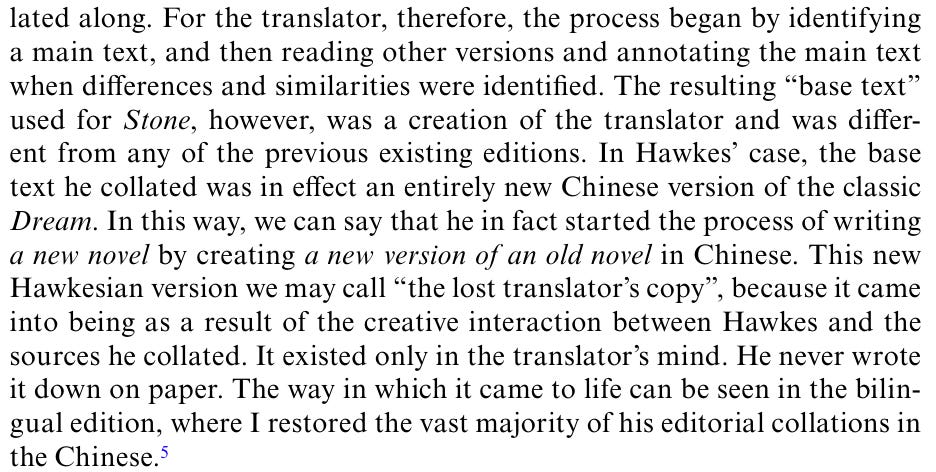

Australian National University Professor Fan Shengyu, who helped put together the bilingual (Chinese and English parallel text) version of The Story of the Stone, actually went as far as to publish an entire book on Hawkes’ translation. This book is called The Translator’s Mirror for the Romantic, and is mostly a hagiography of Hawkes and his translation process.

Despite the fanboy approach, even Professor Fan has to admit that Hawkes created his own version of the book — and insinuates that many of his editorial decisions came out of thin air:

As you can tell, I don’t share Professor Fan’s awe for Hawkes.

On the contrary: I feel strongly that we need a translation of the most commonly used version of the book.

We can’t even begin to enter the textual criticism conversation unless we have an idea of what the 1792 version says. Once we figure out what is going on with the 1792 version of the book, we can then start moving on to other original editions, looking at the various differences.

The problem that we have is that many English speaking scholars of Dream of the Red Chamber let the interesting textual history of the book get in the way of the book itself. Instead of focusing on what the book actually says, they wind up getting lost in the sea of manuscripts and original versions, confusing their readers in the process.

Readers should be able to approach Dream of the Red Chamber as a work of fiction without having to worry about the confusing textual history. In fact, I’d argue that many students interested in the book as a work of classic fiction wind up turned off by all the squabbling over old manuscripts, as well as the never ending accusations of fraud and deception. Let’s worry about what the book says first, and then we can jump into those problems.

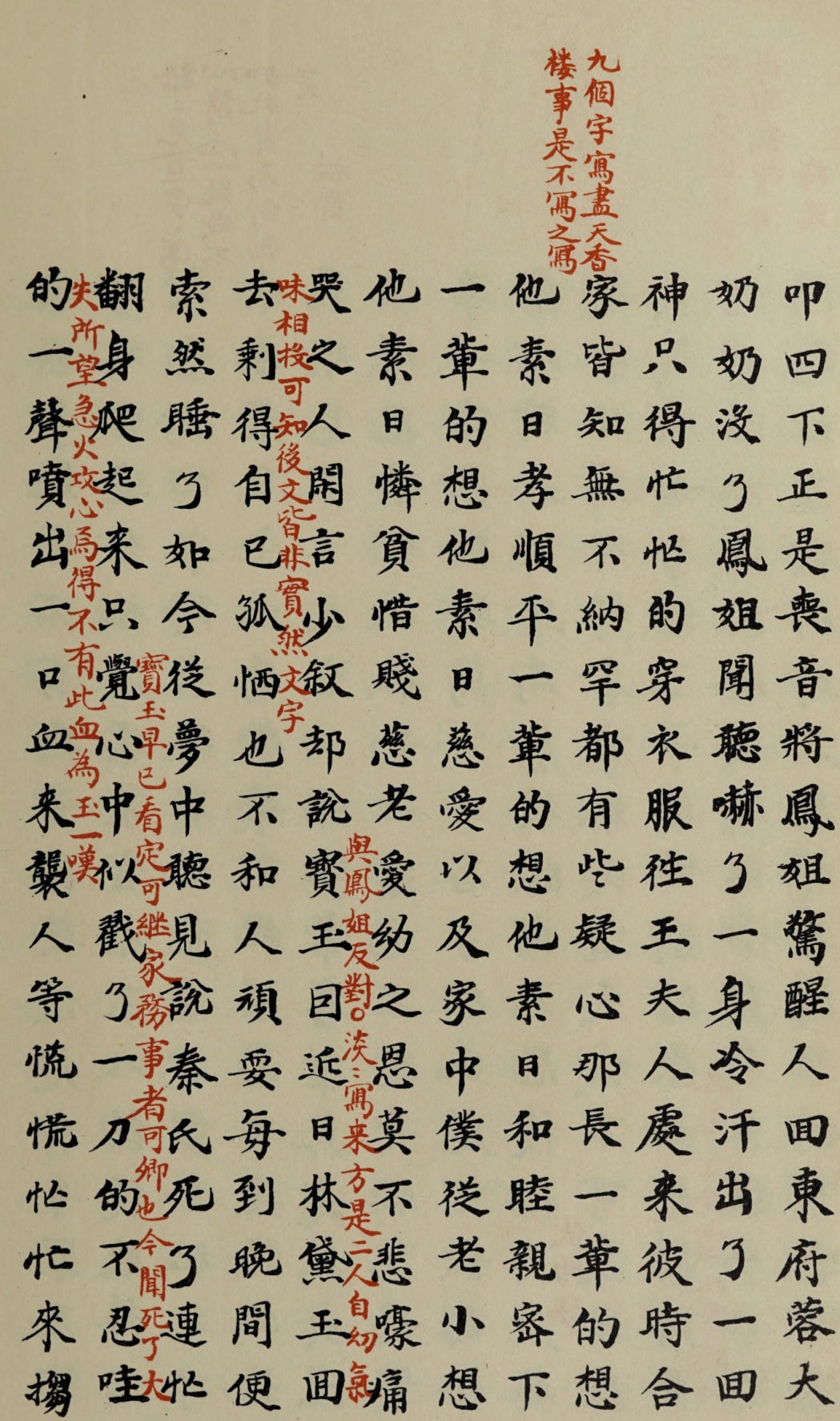

To prove to you that I’m actually using the original 1792 text, I’ve made sure to include screenshots of the original text with every single translation post. Now, if you look closely you’ll notice that there are a bunch of interesting things going on with that text. There’s no punctuation, for example. We’ll talk more about that in a later post.

The Heavenly Mystery

So why am I bringing this up now?

Well, as we saw in yesterday’s text, there’s an interesting section in the first chapter about a “heavenly mystery:”

二仙笑道:「此乃玄機,不可預洩。」

The two divine men laughed: “That’s a heavenly mystery! We can’t reveal it ahead of time.”

Now, I don’t just want to translate the book. I want to also help you understand what in the world it means. And so let’s see if we can figure out what Cao Xueqin is talking about here.

The laughing monks were answering this question that Zhen Shiyin had:

適聞仙師所談因果,實人世罕聞者。但弟子愚拙,不能洞悉明白。若蒙大開痴頑,備細一聞,弟子洗耳諦聽,稍能警省,亦可免沉淪之苦了。

As luck would have it, I overheard both of you immortal masters discussing karma — something that is unusual for mortals to hear. Unfortunately, I’m foolish, and was unable to fully understand what you meant. If you’d be willing to give a fool like me a full explanation, I promise to listen with my full attention. In fact, if I could gain a bit of spiritual awakening, I might be able to escape the pain of karmic suffering.

Zhen Shiyin was asking them about karma. Note that he’s not asking them what will happen in the future. It seems clear to me that he’s asking them about how karma works, hoping that they’ll tell him some deep secret that will help him avoid “the pain of karmic suffering.”

Now, the really fascinating thing about karma that we’ve seen so far in Dream of the Red Chamber is that it’s not divinely decreed. In other words, in the original text the Goddess Who Unveils Illusion doesn’t come out and demand that the fairy plant (who becomes Lin Daiyu) repay her “debt” to the stone (who becomes Jia Baoyu).

This is a really important point, and is something that most Western readers completely miss because of poor translation. The Yangs, for example, make it seem like “the Goddess Disenchantment” (or the Goddess Who Unveils Illusion) ordered Lin Daiyu to go to earth to repay Jia Baoyu for the “debt.” But that’s simply not the case.

The bizarre thing about the relationship between the flower and the stone (or divine servant, or Jia Baoyu, or however you want to refer to him) is that the stone didn’t actually do anything to give the dew to the flower. The dew simply rolled off its back.

In other words — there really wasn’t any debt at all. Lin Daiyu (in her premortal state) is the one who decided that there was a debt, and who decided that she needed to repay the stone by shedding tears.

In my opinion, what Cao Xueqin is telling us here is that fate — or karma, or just the way things turn out, or God’s plan for all His children, or whatever you want to call it — is actually something that we humans create.

In fact, we’re going to see proof of this in the story of Zhen Shiyin. In the next few passages, he’ll come across a catastrophe that is every parent’s worst nightmare.

Zhen Shiyin won’t be able to do anything to prevent the calamity from taking place. However, his fate in the end is clearly determined not by a random (yet awful) event, but, rather, by the way he responds to the event.

In other words, the 玄機, or divine mystery, is that fate, karma, or whatever you want to call it is directly tied to how we respond to the things that happen in our lives. It’s not that heaven decides our fate and that we lay back passively to see what will become of us. We are always in control of how we respond.

Fate And The Versions Of The Novel

The reason why I brought up all the early manuscripts and versions of the text at this point is because the heavenly mystery (玄機) shows us just how ridiculous the speculation around fraud and the author’s “original intent” really is.

I’m way too early in this project to say this — but I happen to know that there are clear textual clues that most of the final 40 chapters were written by a different author. However, the argument that has come up over and over again for the past century that the ending was completely fraudulent is ridiculous.

Cao Xueqin tells us time and time again in the first chapter that the book will be a tragedy in the end. The story of Zhen Shiyin is a clear pattern for what will happen to Jia Baoyu. And, once you realize that the true heavenly mystery (玄機) is the fact that the characters are largely shaping their own fates.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the final 40 chapters are exactly how Cao Xueqin would have written them. However, it does mean that the overall idea is likely the same — and, in my opinion, that’s the most important part.