The Great Chinese Literature Rant

In today’s snippet, the Taoist priest (Kong Kong) argues with the stone, telling the stone that its story will never be taken seriously because it doesn’t follow the conventions of contemporary literature. The stone replies with a ferocious criticism of contemporary mainstream Chinese literature. Cao Xueqin’s famous criticism of Chinese literary culture here reads like something out of the May Fourth Movement – and, interestingly enough, provides a contrast to the tremendous amount of classical and literary references in his book.

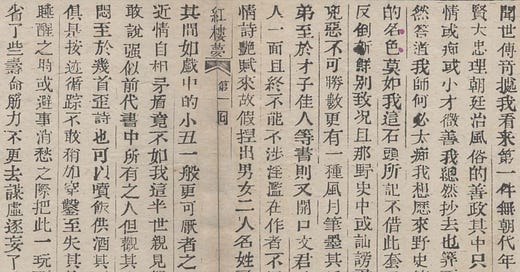

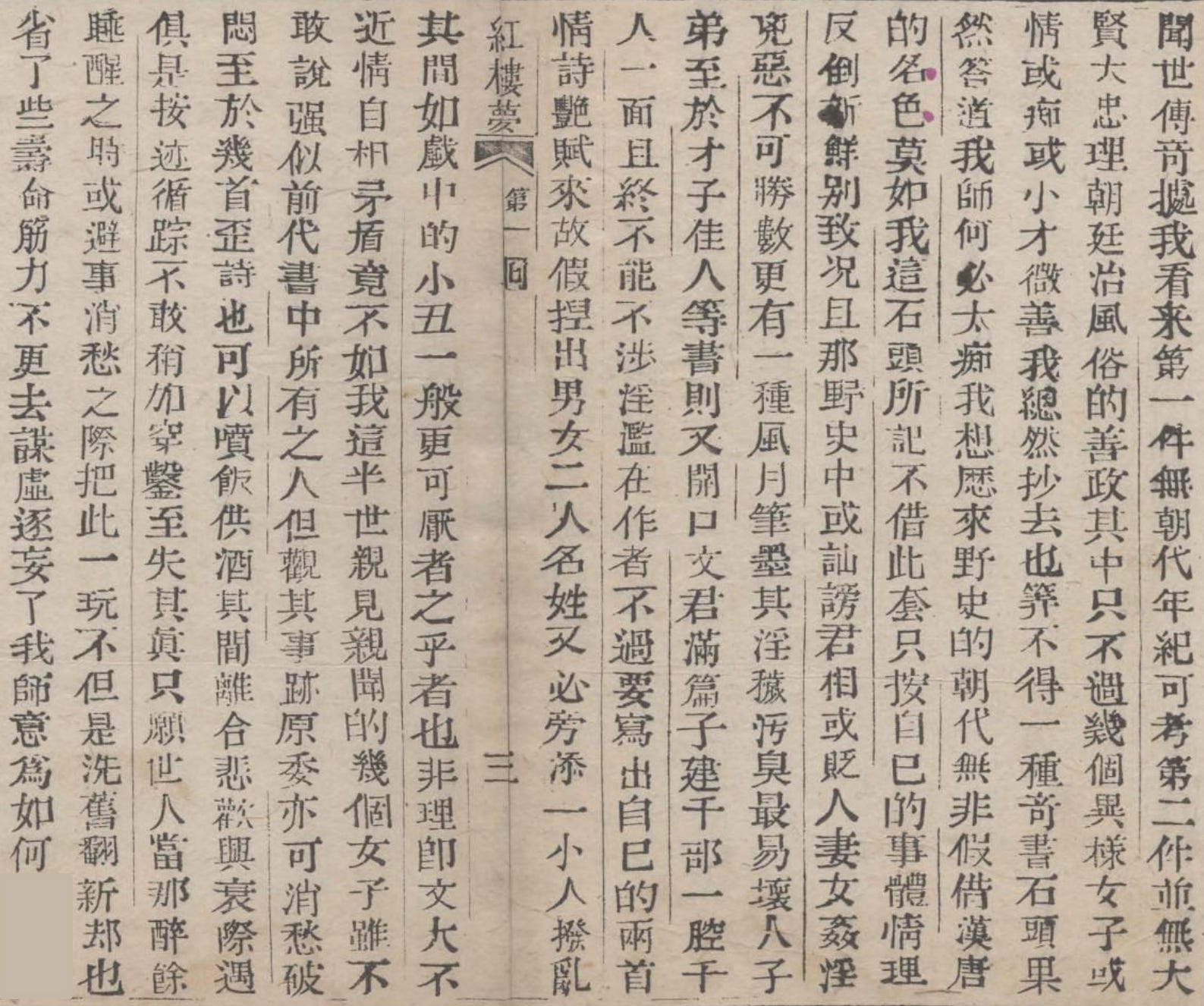

Chinese Text

空空道人看了一回,曉得這石頭有些來歷,遂向石頭說道:「石兄,你這一段故事,據你自己說來,有些趣味,故鐫寫在此,意欲問世傳奇。據我看來,第一件,無朝代年紀可考;第二件,並無大賢大忠理朝廷治風俗的善政,其中只不過幾個異樣女子,或情,或痴,或小才微善:我縱然抄去,也算不得一種奇書。」石頭果然答道:「我師何必太痴?我想歷來野史的朝代,無非假借漢唐的名色;莫如我這石頭所記,不借此套,只按自己的事體情理,反倒新鮮別緻。況且那野史中,或訕謗君相,或貶人妻女,姦淫凶惡,不可勝數,更有一種風月筆墨,其淫穢汙臭,最易壞人子弟。至於才子佳人等書,則又開口文君,滿篇子建,千部一腔,千人一面,且終不能不涉淫濫。在作者不過要寫出自己的兩首情詩豔賦來,故假捏出男女二人名姓,又必旁添一小人,撥亂其間,如戲中的小丑一般。更可厭者,『之乎者也』,非理即文,大不近情,自相矛盾。竟不如我這半世親見親聞的幾個女子,雖不敢說強似前代書中所有之人,但觀其事蹟原委,亦可消愁破悶。至於幾首歪詩,也可以噴飯供酒。其間離合悲歡,興衰際遇,俱是按跡循蹤,不敢稍加穿鑿,至失其真。只願世人當那醉餘睡醒之時,或避事消愁之際,把此一玩,不但是洗舊翻新,卻也省了些壽命筋力,不更去謀虛逐妄了。我師意為如何?

Translation Notes

痴 here is not “foolish” (as in 白癡) or “insane,” but rather “infatuated” or “overly consumed by emotions,” similar to the idiom 如痴如醉 (intoxicated by something; spellbound; fascinated)

縱然 means “even if” or “even though”

野史 refers to unofficial historical texts, in contrast to 正史, or the 24 official histories of ancient China.

訕謗 means to slander.

貶 is to reduce or to lower; it’s used metaphorically here. 貶人妻女 is to debase the wives and daughters of people.

風月 is a term we’ll see come up again in different contexts. It literally means “the gentle breeze and the bright moonlight,” and has obvious romantic connotations that transcend culture. It refers here to romance and love making.

才子佳人 is an idiom meaning “a handsome and talented man and a beautiful woman.” You can still see it in modern Chinese.

文君 refers to Western Han poet 卓文君 Zhuo Wenjun

子建 refers to Three Kingdoms poet 曹子建 Cao Zijian, also known as 曹植 Cao Zhi

情詩豔賦 means “sentimental poems and flowery prose.”

小人 here means “scoundrel” or “villain.” Similarly, 小丑 is a clown.

之乎者也 refers in general to classical Chinese writing. 之, 乎, 者, and 也 are all classical grammatical particles that are absolutely vital to understand if you want to understand classical Chinese. While 之乎者也 can refer more generally to indecipherable speech, it can also refer to a person who knows the Chinese classics well.

按跡循蹤 means following traces and tracks. 按 and 循 both mean “follow,” and 跡 and 蹤 both refer to tracks or footprints. Here this is used to demonstrate that the work is rooted in reality – that there will be no embellishments.

穿鑿 literally means to dig or open up; here it means to give an implausible and far-fetched interpretation of something.

洗舊翻新 means “wash the old and change to the new,” or to refresh and renew.

謀虛逐妄 means “scheme for the empty and chase the illusory,” or to pursue something that doesn’t actually exist. This is one of the major themes of this book – one that we’ll see come up time and time again.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

“Come, your reverence, must you be so obtuse?” is Hawkes’ rendition of 我師何必太痴? I suppose he is playing off the ridiculousness of calling 我師 something as rude as 太痴. I consider the wording here to be really awkward, even if you take it in the 19th century British context that Hawkes obviously loved so much.

That’s not the worst part, though. Hawkes also includes a parenthetical explanation that Kong Kong had correctly deduced that the stone could talk. This is wholly unnecessary, since we established in our last translation passage that the stone was inscribed with its own complete history – clearly indicating its sentient nature.

Hawkes completely omits the references to Zhou Wenjun and Cao Zijian, and then translates “clown” (小丑) as “the chou in a comedy.” This is bizarre, and is difficult for the average reader to understand without at least a footnote. In fact, this, in my opinion, is completely inexcusable. How in the world can you consider a work a translation if you’re not actually translating?

Think about this for a minute. In less than 4 full pages of translation, Hawkes has used one Sanskrit word, three confusing Latin-derived names for holy men, and now an untranslated transliteration of a basic Chinese term that any modern Chinese reader would instantly recognize.

There’s a reason why students and curious readers tend to give up early on the Hawkes translation. The scholars may love it and praise it, but the market rejected it long ago.

Yang

If you thought that Hawkes ripped this passage apart, just wait.

The Yangs have Kong Kong claim that the women have “small gifts and trifling virtues which cannot even compare with those of such talented ladies as Pan Chao or Tsai Yen.” That’s not in the text; or, more precisely, it’s not in the 1792 version of the text, which is the one we’re taking as our base text here. More on that in a later post.

Anyway, Pan Chao is better known as Ban Zhao (班昭), a female Chinese historian and philosopher from around 100 AD. She was undoubtedly extremely talented; in fact, she helped complete the official history of the Han Dynasty (漢書), considered to this day to be one of the most literary and readable of the old dynastic histories.

Tsai Yen must be Cai Yan (蔡琰), an extremely gifted poet and artist of the later Han dynasty.

The Yangs also insert a bit of political commentary of their own: “At present the daily concern of the poor is food and clothing, while the rich are never satisfied,” and so on. This direct political commentary is nowhere in the 1792 version of the novel. I strongly suspect that the Yangs did so for political reasons, likely in order to add in a bit of pro-Maoist rhetoric wherever possible. You could argue that they’re reading a Communist interpretation into the text.

The Yangs also refer by name to “Tsao Tzu-chien, Cho Wen-chun, Hung-niang, Hsiao-yu and the like” at the end of this passage. Tsao Tzu-chien is Cao Zijian, or Cao Zhi, and Cho Wen-chun is Zhuo Wenjun, both of whom are mentioned in the original text. Hung-niang is likely Hongniang (紅娘), a matchmaker from Romance of the Western Chamber (西廂記), which is one of the works that heavily influenced Cao Xueqin. I have no idea why in the world the Yangs would mention her. Finally, Hsiao-yu refers to Huo Xiaoyu (霍小玉), a fictional character in a Tang dynasty story who falls in love with a male character.

It’s hard to figure out precisely what the Yangs meant when they started throwing random names in their translation. Like Hawkes’ insistence on transliterating perfectly ordinary words, the addition of names without context is pretty off-putting to the ordinary reader.

Overall, I’d characterize both “translations” of this passage to be nothing more than a paraphrase. Both translators change the order of the sentences and omit important details.

My Translation

Once he read this and realized the stone had an interesting past, Kong Kong spoke to it. “Brother stone,” he said, “just as you yourself said, your story is pretty interesting. And so it’s been clearly inscribed here to be shared with the outside world.

“However, I see two problems with it. First, it doesn’t refer to a specific dynasty or historical events, which would have lent it authenticity. And second, it contains no references to great sages, loyal ministers, or virtuous policies for governing the court and improving customs. There are only a few extraordinary women: some are sentimental, some are consumed by emotion, and some possess small talents and minor virtues. Even if I were to copy it all down, it still wouldn’t count as an extraordinary book.”

“Why are you so naive, my lord?” the stone replied, unexpectedly. “I think there are already more than enough unofficial histories that misuse names from the Han and Tang Dynasties. They’re nothing like my story at all. My story follows its own events and logic, making it fresh and unique.

“What’s more, some of those unofficial histories slander rulers and ministers, while others defame people’s wives and daughters. They are filled with countless tales of debauchery and wickedness. There is also a kind of romantic writing that is so obscene and filthy that it’s sure to corrupt the minds of young people.

“As for books about talented scholars and beautiful ladies, they’re all filled with stories about Zhou Wenjun and Cao Zijian. Thousands of books contain the same tone, and their thousands of characters share the same face. In the end, they all end up indulging in lust and excess.

“Their authors only want to showcase a few of his own sentimental poems and romantic verses, and so he makes up the names of a man and a woman, and inevitably adds a villain on the side to stir up trouble between them. They’re just like the clowns in the plays.

“And even worse is their excessive use of classical phrases, which are overly moralistic, overly literary, are completely detached from human emotions, and are often self-contradictory.

“None of that even comes close to the women I’ve seen and spoke to myself during my lifetime. Though I don’t dare say they are as strong as the people in earlier books, when you examine the details of their stories, they can dispel sorrow and relieve boredom.

“As for the few clumsy poems in this work, they can also be amusing over a meal or when accompanied by a drink. The joys and sorrows, partings and reunions, and rises and falls within the story all follow the patterns of real life. I don’t dare fabricate the slightest bit, lest the story lose its authenticity.

“I only hope that when my readers are in a tipsy state after drinking, when they’re awake from sleep, when they want to escape troubles, or when they want to dispel sorrow, that they’ll pick it up for a moment of enjoyment. Not only will it refresh their minds, but it will also help them save the time and energy they might otherwise spend chasing empty dreams and illusions.

“What do you think of this, sir?”

There’s actually a lot to talk about here — more than we’ll be able to get to in tomorrow’s commentary post. Cao Xueqin’s biting criticism of China’s classical literary culture is surprisingly frank. The great irony, though, is that Cao Xueqin is actually guilty of the same sins he accuses others of committing. Keep this passage in mind; we’ll come back to this theme later.