The Dream Starts

The first paragraph of Dream of the Red Chamber is a somewhat cryptic commentary on the overall scope, meaning, and symbolism of the work itself. Its obvious use of homophones in names defies translation, and its religious and philosophic allusions aren’t easy to grasp at first. This is probably why so many translations of Dream of the Red Chamber simply omit this paragraph. Of course, you can’t simply ignore this paragraph. Not only was it written for a reason, but it also draws a direct personal link between the author and his work – a link that has been debated by scholars for centuries.

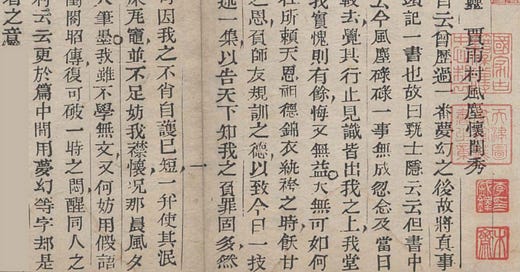

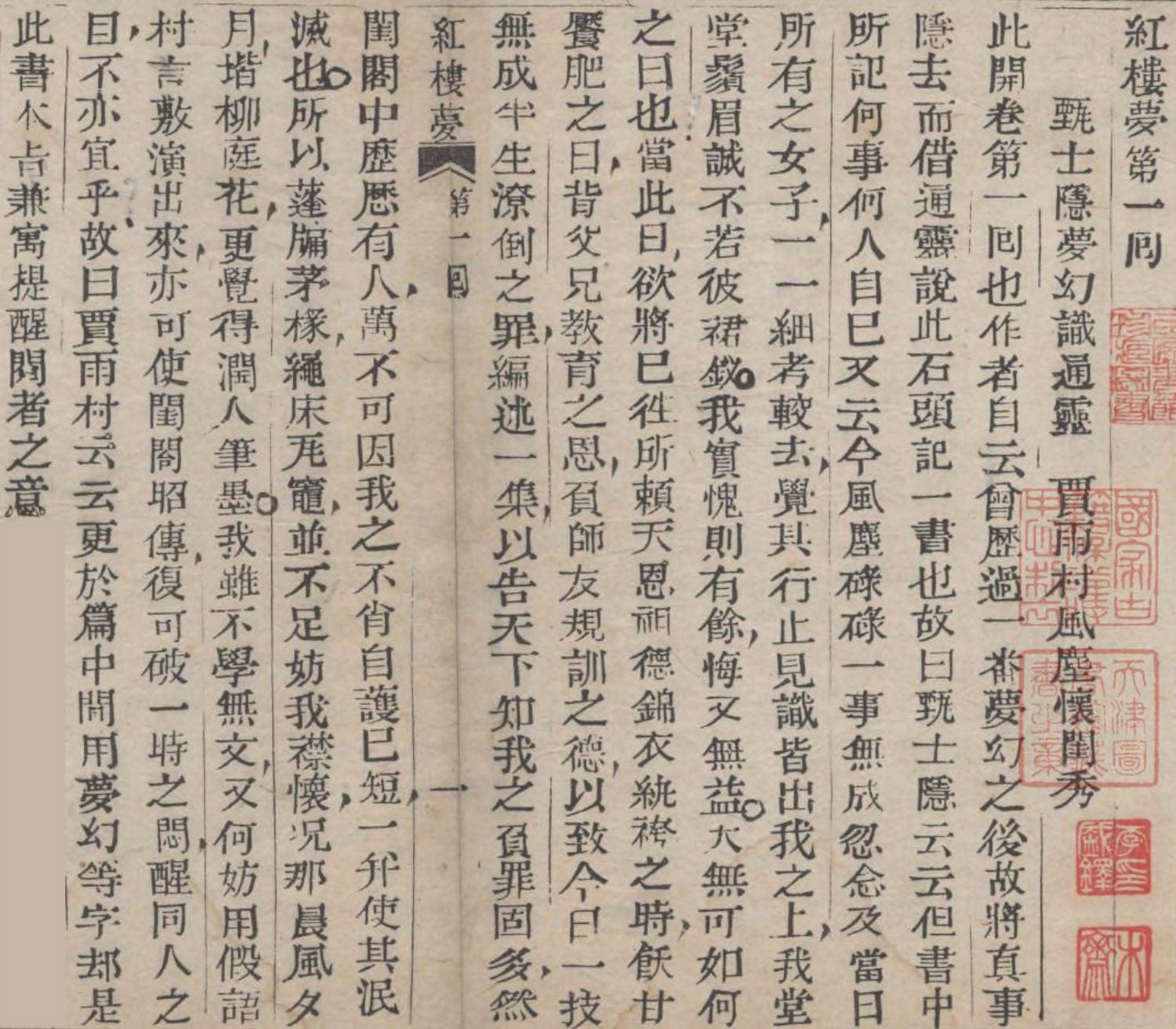

Chinese Text

第一回 甄士隱夢幻識通靈 賈雨村風塵懷閨秀

此開卷第一回也。作者自云曾歷過一番夢幻之後,故將真事隱去,而借「通靈」說此《石頭記》一書也,故曰「甄士隱」云云。但書中所記何事何人?自己又云:今風塵碌碌,一事無成,忽念及當日所有之女子,一一細考較去,覺其行止見識皆出我之上,我堂堂鬚眉,誠不若彼裙釵。我實愧則有餘,悔又無益,大無可如何之日也!當此日,欲將已往所賴天恩祖德錦衣紈袴之時,飫甘饜肥之日,背父兄教育之恩,負師友規訓之德,以致今日一技無成,半生潦倒之罪,編述一集,以告天下。知我之負罪固多,然閨閣中歷歷有人,萬不可因我之不肖自護己短,一併使其泯滅也。所以蓬牖茅椽,繩床瓦灶,並不足妨我襟懷。況那晨風夕月,階柳庭花,更覺得潤人筆墨。我雖不學無文,又何妨用假語村言敷衍出來,亦可使閨閣昭傳,復可破一時之悶,醒同人之目,不亦宜乎?故曰「賈雨村」云云。更於篇中間用「夢」「幻」等字,卻是此書本旨,兼寓提醒閱者之意。

Translation Notes

通靈 could mean a number of things. “Spiritual enlightenment” might be a better translation than “spiritual communication,” though it doesn’t make much sense in this context. Cao Xueqin seems to be referring to the fact that he won’t flat out tell his reader what he’s trying to say with his story; instead, it is up to the reader to use a variety of interpretive tools to decipher the literary techniques he employs. Again, language like this in the very first paragraph of a major literary work is pretty unique. This also refers to 通靈寶玉, which we’ll get to later in this chapter.

此開卷第一回也 is a phrase that apparently does not exist in any other classical Chinese works. I have not been able to find any equivalent phrases elsewhere. Not even abbreviated forms, such as 開卷第一, tend to show up in searches on websites such as the Chinese Text Project. It’s a very odd way to begin a novel, and does not seem to have an equivalent anywhere in the world of classical Chinese iction.

夢幻 literally means “a dream.” Because of this, there is some confusion about the phrase 一番夢幻, which literally means “a series of dreams.” You could figuratively consider it to be “a sequence of dreamlike experiences,” which might match up better with the overall theme of the book. Here, I decided on the more figurative translation because the entire work refers to dreams. In other words, my interpretation here is that Cao Xueqin is referring to the entire book when he cites 一番夢幻, and not just a specific series of dreams contained in the beginning of the first chapter.

故曰「甄士隱」云云 is the first of two direct references to the names of characters. The name 甄士隱 is a homophone with the phrase 真事隱 – a phrase that Cao Xueqin just used in this same sentence (“將真事隱去,” or “he decided to hide the truth”).

堂堂鬚眉 (“grand and majestic beard and eyebrows,” referring to a dignified and imposing man) is a phrase you’d expect to be a common idiom, but it appears to be unique to this portion of the book. Here it is contrasted directly with 裙釵, “skirts and hairpins,” which clearly refers to women. We’ll see a lot of comparisons of this type as we progress through the book.

大無可如何之日也 literally means “this is a day of utter hopelessness.”

閨閣 means boudoir, or a woman’s bedroom. Boudoir, which is a word of French origin, is no longer common in English literature; I’ll either translate it literally as “bedroom” or will translate it in the proper context. Here 然閨閣中歷歷有人 refers to the many women the author once knew: literally, “the boudoirs were filled with people.”

不亦宜乎 is a direct quote from the Confucian Analects, and shows up numerous times in Mencius and other classical Confucian phrases. It’s a rhetorical question, something along the lines of “isn’t that suitable?” or “isn’t that appropriate?” The use of such a stilted phrase in this somewhat formal introduction is absolutely deliberate. As we’ll soon see, Cao Xueqin is fascinated with subverting expectations, and has written a book that is decidedly not Confucian.

故曰「賈雨村」云云 is the second example we have of a name that includes a hidden meaning. Cao Xueqin is telling us here that he chose the name Jia Yucun as a reminder that there is no problem using “ordinary language” (often translated as “rustic language”) to tell his story. 賈雨村 is a homophone for 假語村 (“ordinary” or “rustic” language), which comes from the phrase 又何妨用假語村言敷衍出來 in the sentence right before this one. Just like we saw with 甄士隱 earlier in the paragraph, the name 賈雨村 is a play on words that is intended to remind the reader of the purpose of the book. This is also an indication that the names used in this book are intended to be symbolic.

更於篇中間用「夢」「幻」等字,卻是此書本旨,兼寓提醒閱者之意 is not difficult to translate, but is difficult to understand. The author doesn’t specify here precisely what words like “dream” (夢) and “illusion” (幻) are supposed to remind the reader of. It is true, however, that Dream of the Red Chamber is filled with references to dreams and illusions and their relation to reality as described in the book. But the task here is not merely to differentiate what is a dream from what is real. Instead, it seems that we’re supposed to discover precisely what it is that Cao Xueqin wants us to remember.

Translation Critique

David Hawkes and John Minford The Story of the Stone

David Hawkes does not include this paragraph in his proper translation of the novel. Instead, it is hidden in the introduction: pages 20 and 21 of the Penguin Classics paperback copy. Naturally, most readers will skip Hawkes’ 31 page introduction.

The Chinese-English bilingual version of The Story Of The Stone published by Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press includes this introductory paragraph: see pages 20 and 21 for the English version, and page 42 for the Chinese. Neither the English nor Chinese versions offer a complete translation of the paragraph.

Hawkes quotes this paragraph as “Cao Xueqin’s own words,” and yet does not include it in his actual translation of the book.

His translation is also bizarre: “it suddenly came over me that those slips of girls – which is all they were then – were in every way, both morally and intellectually, superior to the ‘grave and mustachioed signior’ I am now supposed to have become.” This is the first time (but, obviously, not the last) that we’ll see Hawkes mix his interpretation of the text in with the original text.

I find the “slips of girls” statement, along with the “which is all they were then” invention, to be both distasteful and inappropriate. Cao Xueqin is not denigrating these women by referring to them as “彼裙釵,” and to insinuate this meaning is to completely misread the text.

The same goes for the description of inspiration despite poverty. Hawkes writes in “But these did not need to be an impediment to the workings of my imagination” after mentioning the thatched roof and so on. This is nice – but it simply does not exist in the original text!

In short – not only does Hawkes not translate the full text, but he also starts adding in things that are simply not in the original.

Yang Hsien-Yi and Gladis Yang A Dream Of Red Mansions

The Yangs translate the beginning as “he tried to hide the true facts of his experience by using the allegory of the jade of ‘Spiritual Understanding.’” However, there’s nothing in the original that indicates an “allegory.” This translation involves inserting an interpretation into the text that isn’t in the original.

In the footnotes, the Yangs indicate that “Chen Shih-yin” is a “homophone for ‘true facts concealed,’” and that “Chia Yu-Tsun” is a “homophone for ‘fiction in rustic language.’”

The Yangs do not translate the final sentence about using words like “dream.” Hawkes, by the way, also omitted that sentence, likely deliberately. As we’ll see in tomorrow’s commentary text, this is a big problem.

My English Translation

Chapter 1: In a dream, Zhen Shiyin achieves spiritual insight; in the world, Jia Yucun longs for a refined woman

This is the first chapter of this book.

The author says that, after having had a kind of dreamlike experience, he decided to hide the truth, relying instead on “spiritual communication” to write this book, The Story of the Stone. This is why he used names such as Zhen Shiyin.

But what about the events and characters in this book? Again, the author himself remarked:

“Seeing that I’ve accomplished nothing in the midst of the hustle and bustle of this world, I started to think about the women I used to know. When I really thought about it, I realized that their actions and insights far surpassed my own. Though I am a grown man with a mustache and beard, I am truly no match for their skirts and hairpins. I feel deeply ashamed – but regrets help nothing. Alas, there’s nothing I can do about it now!

“Right now I just want to remember those days, back when I enjoyed the blessings of heaven and the virtue of my ancestors, when I wore luxurious clothes and tasted delicious food – those days when I disregarded the kindness of my parents and brothers and neglected the admonitions of my teachers and friends. Those happy days all led to the wasted life I enjoy now: a lifetime of destitution. I’ve compiled all of this in a book to warn the world of my fate.

“I know that I have many faults – and yet the memory of those girls remains strong. It would be awful to let their memories fade away completely just to hide my own shortcomings!

“And so even my simple hut and clay stove won’t discourage me. But that’s not all: the breeze in the morning, the moon in the evening, the willows on the steps, the flowers in the courtyard – all these things keep the ink in my brush flowing. Sure, I may be uneducated and poor at writing – but why can’t I use ordinary language to explain things? Such language would illuminate the stories of those girls, dispel moments of boredom, and might even help others like me to wake up. Isn’t that appropriate?

“This is why I use names such as Jia Yucun.

“In the same vein, I often use words like ‘dream’ and ‘illusion’ in this book. These words reflects the book’s main theme, and serve as a reminder to my readers.”

Did I get something wrong? Did I miss something important? Do you like what you’ve read? In any case, please leave a comment!