The Crazy Monk And Priest Intervene

Zhen Shiyin’s attempt to follow the monk and priest into the Illusory Realm of the Great Void ends up failing. He wakes up, forgets most of the dream, and decides to take his daughter Yinglian outside to see a festival parade. The monk and priest approach him suddenly, laughing wildly. They demand that he cut all ties with his daughter, and then chant an ominous warning to him when he ignores them.

Chinese Text

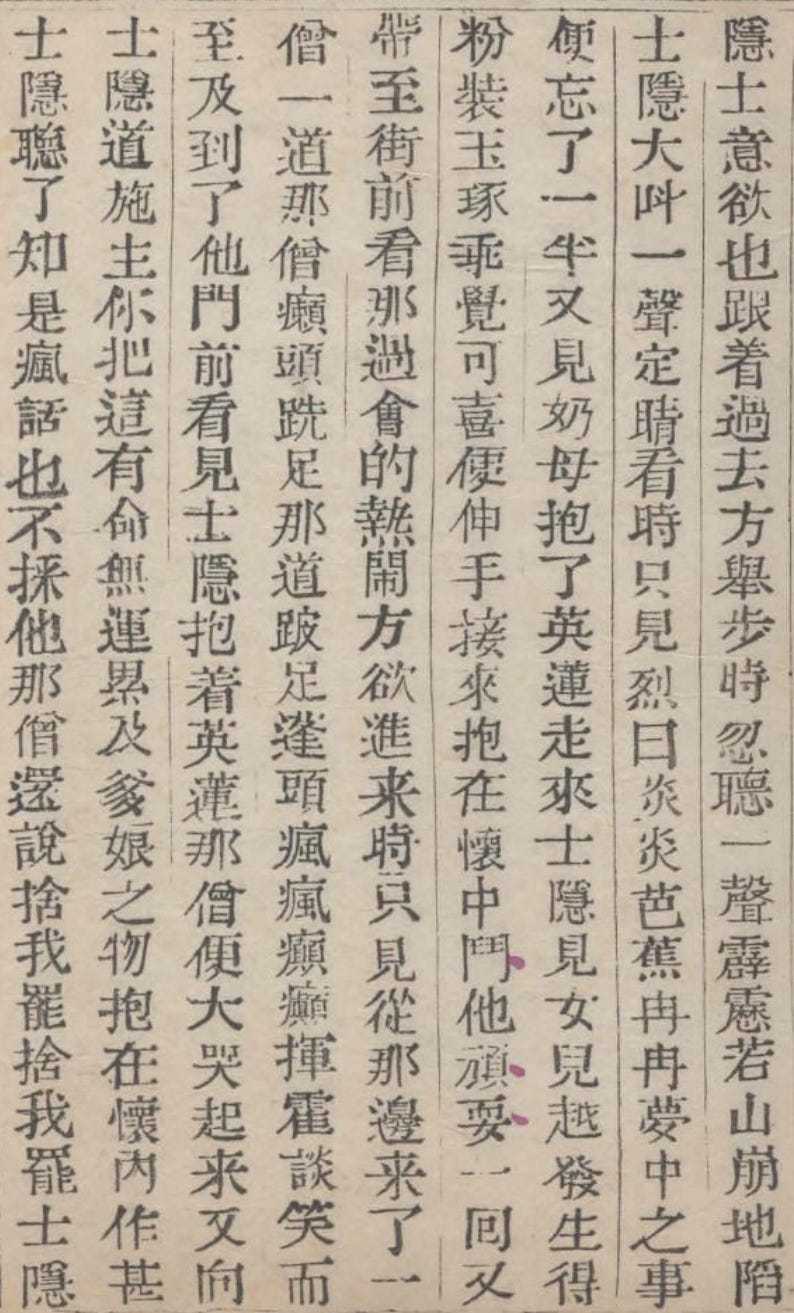

士隱意欲也跟著過去,方舉步時,忽聽一聲霹靂,若山崩地陷。士隱大叫一聲,定睛看時,只見烈日炎炎,芭蕉冉冉,夢中之事便忘了一半。又見奶母抱了英蓮走來。士隱見女兒越發生得粉妝玉琢,乖覺可喜,便伸手接來,抱在懷中,鬥他玩耍一回,又帶至街前看那過會的熱鬧。方欲進來時,只見從那邊來了一僧一道。那僧癩頭跣足,那道跛足蓬頭,瘋瘋癲癲,揮霍談笑而至。及到了他門前,看見士隱抱著英蓮,那僧便大哭起來,又向士隱道:「施主,你把這有命無運累及爹孃之物抱在懷內作甚?」士隱聽了,知是瘋話,也不睬他。那僧還說:「舍我罷!舍我罷!」士隱不耐煩,便抱女兒轉身才要進去。那僧乃指著他大笑,口內唸了四句言詞,道是:

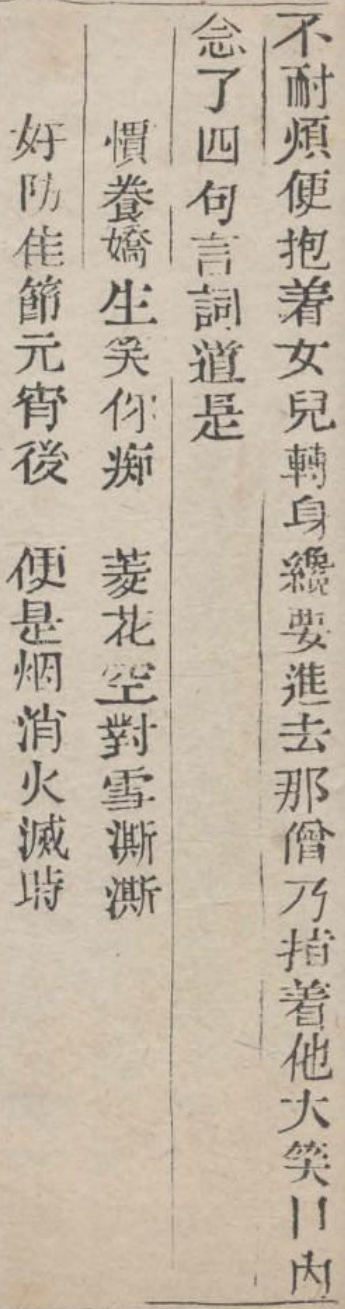

慣養嬌生笑你痴,菱花空對雪澌澌。好防佳節元宵後,便是煙消火滅時。

Translation Notes

霹靂 is the clapping sound of thunder.

烈日炎炎,芭蕉冉冉 is a poetic couplet. The intense heat (炎炎) of the fierce sun (烈日) is contrasted directly with the soft swaying (冉冉) of the banana plants (芭蕉). This is pretty common in classical Chinese literature: authors would combine two very different adjectival phrases to give a scene rich in sensory and emotional layers.

越發生得 is confusing if you’re mostly used to modern Chinese grammar. 越發 here is an adverb: “all the more,” “even more,” “increasingly,” and so on. 生 here doesn’t mean “to be born,” but, rather, “to grow” or “to naturally become.” 得 is a descriptive complement, just as it is in modern Chinese. In other words, 越發生得 here is the same as 長得越來越 (became more and more) in modern Chinese. Yinglian is becoming cuter and more doll-like.

粉妝玉琢 refers literally to porcelain-like beauty, as if Yinglian looked like white powdered jade. “Doll-like” in this situation is probably a more natural phrase in English.

乖覺可喜 combines “well-behaved and quick witted” (乖覺) with “adorably pleasing” (可喜). Yinglian is an intelligent and cute child.

過會 is a traditional festival procession or festival parade, often with floats, performances, and so on.

從那邊 is really vague here. It’s not clear where the monk and priest are coming from.

癩頭跣足 and 跛足蓬頭 are obviously parallel passages: “scabby head and bare feet” combined with “unable to walk and with a disheveled head.” This passage demonstrates the lack of worldly concerns for both the priest and the monk. This is also an absurd contrast: the two men can scarcely walk, and yet are easily able to travel from the celestial realm to earth.

瘋瘋癲癲 means “crazy.” Cao Xueqin is telling us here that these aren’t serene and kind religious figures. The monk and priest seem to be totally crazy. 揮霍談笑 expands this idea further: they were talking wildly and laughing loudly.

施主 means “benefactor” or “alms giver.”

有命無運 literally means “with a life but without good luck.” 命運, by the way, means “fate.” It’s as if they’re saying that Yinglian was born under an unlucky star.

累及爹孃 means to burden one’s parents. Be careful here: 累及 does mean “implicate” in a modern or legal sense, but, in this passage, the two characters should be considered separately. 累 means “to tire,” or “to burden,” and 及 connects it directly to 爹孃 (mother and father).

舍我罷 is kind of tricky to translate. 我 here doesn’t mean “me” (that would make no sense), but, rather, is used contextually: “the one I am speaking of.” 罷 is am emphatic particle: this is not a request by the monk, but a command.

菱花 is a kind of flower – the water caltrop, or water chestnut. It’s a plant that grows in water in East Asia with a horn-like nut. This is a direct reference to Yinglian, whose name means “heroic lotus.” Yinglian’s name will soon be changed to 香菱 (fragrant water caltrop) in direct reference to this line.

澌 means to dry up. In this poem, the lotus withers in the face of the snow.

The phrase 好防佳節元宵後 (beware the end of the Lantern Festival) not only refers to Yinglian’s fate, which will soon be realized, but ultimately also to the fate of the Jia family. We’re a few dozen chapters away from that point, but we’ll see it eventually.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

“Give her to me!” is what the monk demands in Hawkes’ version. It technically works grammatically (it assumes that the Chinese phrase should be 舍於我罷, with the 於 implied), but there are interpretive issues. The monk doesn’t want to have control over Yinglian; rather, he’s telling Zhen Shiyin to sever his attachment with her.

The biggest problem with this translation is that there’s no reason for the monk to want to take custody of the child; however, there absolutely is a reason why the monk would want Zhen Shiyin to give up his strong affection for his child, as if it were his tie to the world. Remember that we just saw Zhen Shiyin beg the same monk and priest to let him know what he needs to do to overcome the pain of karmic rebirth. This is likely the answer to his question – though it’s completely absurd.

Hawkes translates the final poem as:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dream of the Red Chamber to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.