Repaying The Debt With Tears

We’ve got another deceptively simple passage today. Zhen Shiyin’s vision continues. Today he hears the Buddhist monk explain how the Crimson Pearl Fairy Plant (who becomes Lin Daiyu) is so grateful for the dew that came from the Heavenly Jade Servant (who becomes Jia Baoyu) that she offers to follow him to earth. The only way she can think of to repay him for watering her with the sweet dew that gave her life is to shed tears — something that Lin Daiyu does over and over again in the novel. And, as you probably guessed, there’s a lot of symbolism going on.

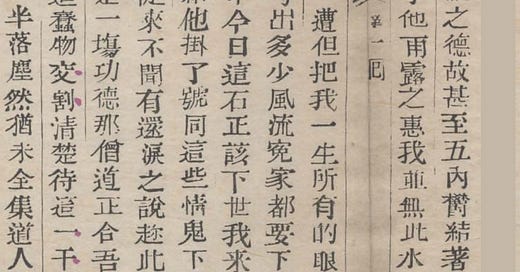

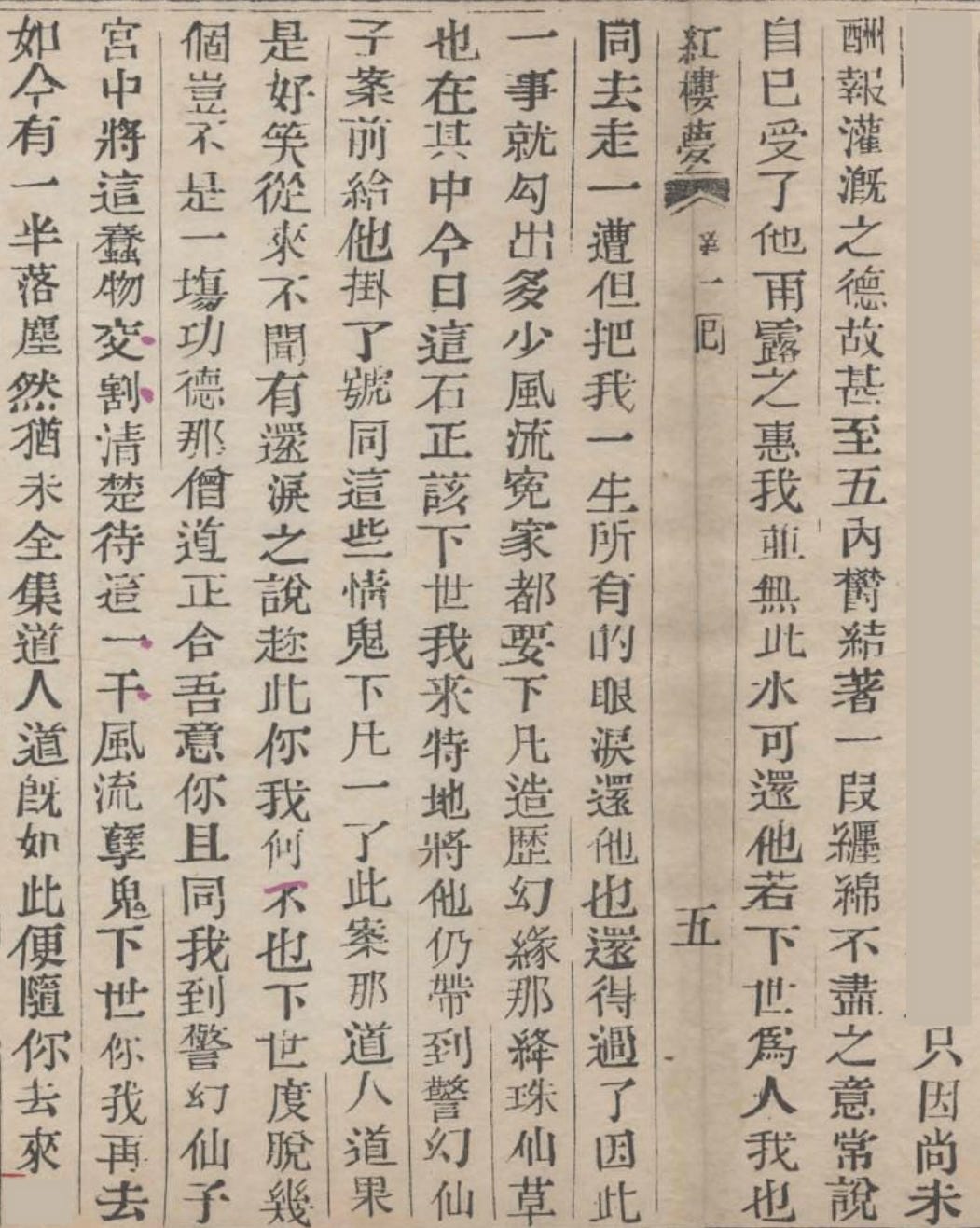

Chinese Text

「只因尚未酬報灌溉之德,故甚至五內鬱結著一段纏綿不盡之意,常說:『自己受了他雨露之惠,我並無此水可還;他若下世為人,我也同去走一遭,但把我一生所有的眼淚還他,也還得過了!』因此一事,就勾出多少風流冤家都要下凡,造歷幻緣。那絳珠仙草也在其中。今日這石正該下世,我來特地將他仍帶到警幻仙子案前,給他掛了號,同這些情鬼下凡,一了此案。」那道人道:「果是好笑,從來不聞有還淚之說。趁此你我何不也下世度脫幾個,豈不是一場功德?」那僧道:「正合吾意。你且同我到警幻仙子宮中,將這蠢物交割清楚。待這一干風流孽鬼下世,你我再去。如今有一半落塵,然猶未全集。」道人道:「既如此,便隨你去來。」

Translation Notes

灌溉 literally means to irrigate. It’s obvious from the context here that this is talking about the 甘露 mentioned earlier.

五內 refers to the “five viscera:” the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys. Here it’s referred to metaphorically, meaning the entire emotional being of the woman. However, the use of this specific language ties the woman’s suffering to medical reality: in other words, this isn’t just something abstract.

鬱結 is “to be pent up” or “to suffer from pent-up frustrations.”

纏綿 is “entangled” or “caught up.”

造歷幻緣 is tricky. 造 is obvious – to create, though in the Buddhist sense of creating karma through one’s own actions. A good Chinese dictionary will likely tell you that 造歷 means to establish a calendar, but that’s clearly not what we’re talking about here. 造歷 is to create experiences, and seems to be linked to the Buddhist concept of Saṃsāra (संसार), or the karmic cycle. 幻, as usual, refers to something illusory or imaginary, and 緣 refers to serendipitous fate, or lucky chance – a word with clearly romantic connotations (which you can see in modern Chinese words like 緣分, or “romantic fate”).

Here the souls (多少風流冤家) caught up in the bond between the stone and the woman are drawn into the world (要下凡; 勾出 earlier in the sentence conveys the concept of being drawn down into something) to go through an endless karmic cycle (造歷) chasing after illusory fate (幻緣). Basically, their lives will be spent chasing in vain after meaning and purpose.

情鬼 literally means “love ghost” or “romantic ghost.” It refers specifically to 風流冤家, which we’ve already covered.

度脫 is a Buddhist phrase here – this refers to delivering someone (度, which is to “ferry across” – we’ve seen that metaphor before) from the cycle of rebirth to enlightenment.

交割 is to settle a transaction (i.e. something financial). The transaction to be settled is the one of the 蠢物, which is the stone.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

Hakes states that Disenchantment (who we call the Goddess Who Unveils Illusion) is the one who decided to send everybody down to earth. I’m not certain that I understand why Hawkes so desperately wants to ascribe that act or decision to somebody. The text doesn’t support that translation, though it’s a valid interpretation.

In my mind, the way to understand this is that the Goddess is simply part of the celestial bureaucracy. Perhaps she’s the one who makes the decisions, or perhaps not. At any rate, because of the way things work, the monk and priest need to take the stone to her desk for registration before it can enter the mortal world.

Hawkes also continues to have his characters refer to the stone as a creature and not a thing.

Yang

There are a lot of issues here.

As I noted in our last translation post, the Yangs decided to completely change the order of sentences here. It’s not really possible to follow this passage in their translation alongside the original; they completely rewrote the section.

In the Yang version, “Shen Ying” (i.e. the stone, or 神瑛侍者) asked the “Goddess of Disenchantment” to allow him to go to earth:

Shen Ying was seized with a longing to assume human form and visit the world of men, taking advantage of the present enlightened and peaceful reign. He made his request to the Goddess of Disenchantment, who saw that this was a chance for Vermillion Pearl to repay her debt of gratitude.

I’ve read through the original text up to this point very carefully. The Yang version is completely incorrect because of the following 3 facts:

The stone never asks to become mortal. Instead, it’s the Buddhist monk that offers the stone a mortal adventure. In other words — Jia Baoyu quite literally never asked to be born.

The Crimson Pearl Fairy Plant wants to repay the debt. The Yangs mischaracterize this relationship by making it look like the Goddess Who Unveils Illusion (警幻仙子) decides that making “Shen Ying” mortal would give the Vermilion Pearl a chance to repay the debt. This isn’t true at all; in fact, as you can see in today’s translation, it’s actually the Vermilion Pearl (絳珠仙草) who comes up with the idea.

The Goddess has nothing to do with the debt. The “debt” between 神瑛侍者 and 絳珠仙草 turns into a direct link between Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu, which we’ll see as the book progresses. Lin Daiyu’s only way to thank Jia Baoyu (who was the premortal stone) for giving her the dew of life is to shed tears for him — something she does a lot of. The important thing to understand, though, is that Lin Daiyu enters into this debt willingly, not because a Goddess demands that she do so.

The mistranslation by the Yangs here isn’t a little error. It fundamentally changes the meaning of the book.

The Yangs also include a full paragraph that has no backing in the original text:

“The old romances give us only outlines of their characters’ lives with a number of poems about them,” said the monk. “We’re never told the details of their intimate family life or daily meals. Besides, most breeze-and-moonlight tales deal with secret assignations and elopements, and have never really expressed the true love between a young man and a girl. I’m sure when these spirits go down to earth, we’ll see lovers and lechers, worthy people, simpletons and scoundrels unlike those in earlier romances.”

This is a Marxist addition — and, I believe specifically one designed to give the book a Maoist taste. There are three major problems with this paragraph:

The novel is not about “ordinary people.” None of the characters in this novel are ordinary — not even the occasional peasants from rural areas that make an appearance. The true main characters — the so-called “金陵十二釵,” or the cast of girls who we’ll meet before long — are anything but “ordinary.” They are literate, educated, and are extremely talented at creating poetry. The point of the book is not to extol the common person. That’s an interpretation that the Yangs read into the novel.

The book has nothing to do with “true love.” The bond between Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu that we just discussed — the debt that has to be repaid with tears — is not a bond of love. It’s one of doomed obsession, of emotions that have gone out of control. We’ll see that as we slowly progress through the novel.

Cao Xueqin did not write a moralistic novel. Talk of “lechers,” “simpletons,” “scoundrels” and so forth creates an overly simplistic look at the book. At the end (and who knows how many years it will take us to reach that point?), we’ll have to ask ourselves whether Jia Baoyu is actually a hero or a villain, and whether Lin Daiyu is actually a tragic genius or a self-destructive neurotic.

The beauty of this novel is that it defies the sort of stereotypical label that Marxist literary theory tends to place on artistic works. And this is precisely why the Yangs constantly read their Marxist interpretations into the novel.

My Translation

“But, because she had not yet repaid the kindness of the nourishing dew, an endless entanglement lay knotted up inside her. ‘I received the gift of his life-giving rain,’ she would often say, ‘but I possess no water to return to him. If he comes into the mortal world, I’ll go along with him. I’ll use every tear I shed to repay him – that should settle my debt!’

“And so this single bond drew countless love-stricken souls into the mortal world – forever chasing after illusory love. That Crimson Pearl Fairy Plant was among them.

“Now it’s time for that stone to journey to earth. In fact, I’m taking him to the Goddess Who Unveils Illusion’s registry desk right now to have him registered and sent down to mortality with these love ghosts. That will close this case.”

“That’s pretty funny,” replied the Taoist priest. “That’s the first time I’ve ever heard of ‘repaying with tears.’ Why don’t we go down too and try to deliver a few souls? Wouldn’t that be a virtuous deed?”

“My thoughts exactly!” said the Buddhist monk. “Come with me to the Palace of the Goddess Who Unveils Illusion. Let’s finish up the account of this stupid thing. Wait for these evil amorous spirits to go to the earth first – then you and I can go down. Half of the souls have already taken up the dust of the world by now, yet not all are accounted for yet.”

“Sounds fine,” replied the Taoist priest. “I’ll go down and come back with you.”

Are we finally going to get to the “real” story? Are you sick of the philosophic introduction? Let me know in the comments!