Jia Yucun The Poet

We’ve got another extended passage today. This one includes three separate poems, which we’ll consider together in a longer commentary post tomorrow. This is the first example we’ve seen of how Cao Xueqin uses poetry to describe character. Everything in Jia Yucun’s poems say something about him, from the relatively simple language he uses to the wild ambition he unintentionally displays.

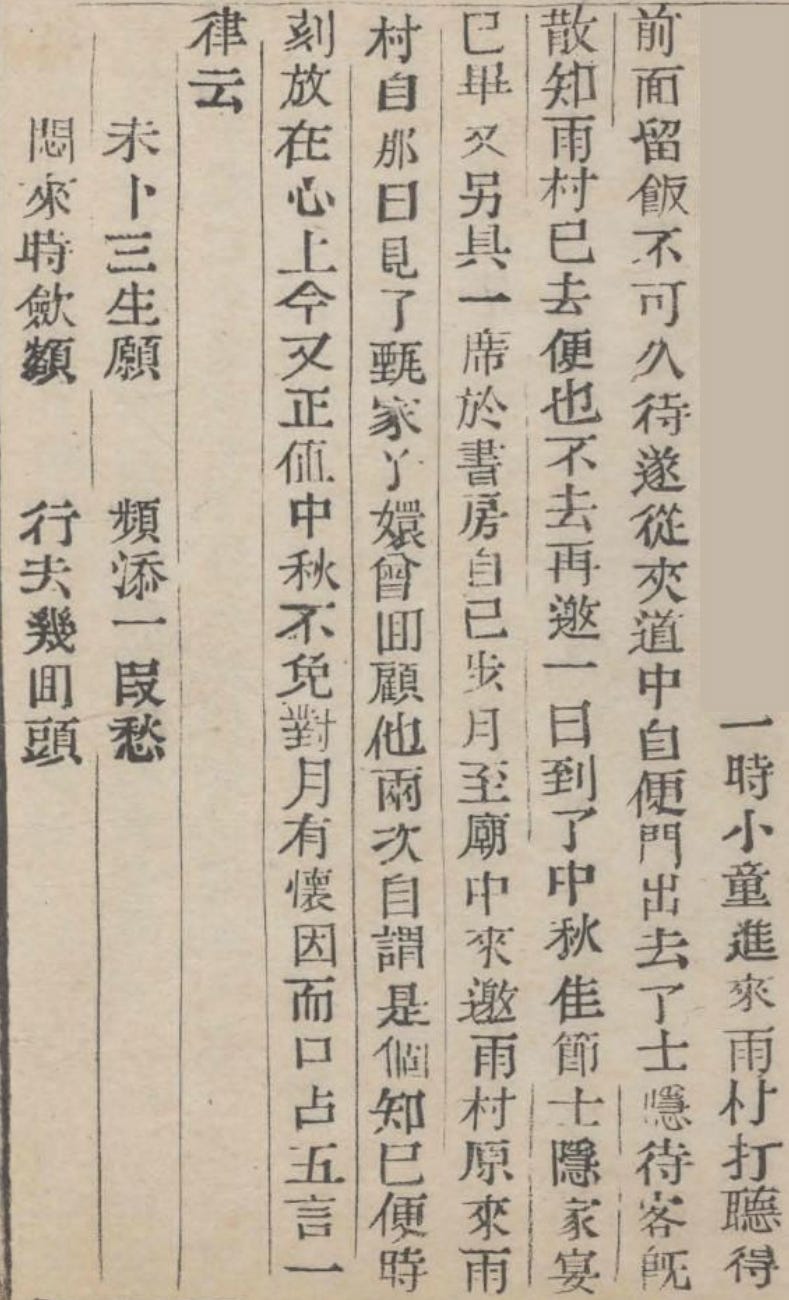

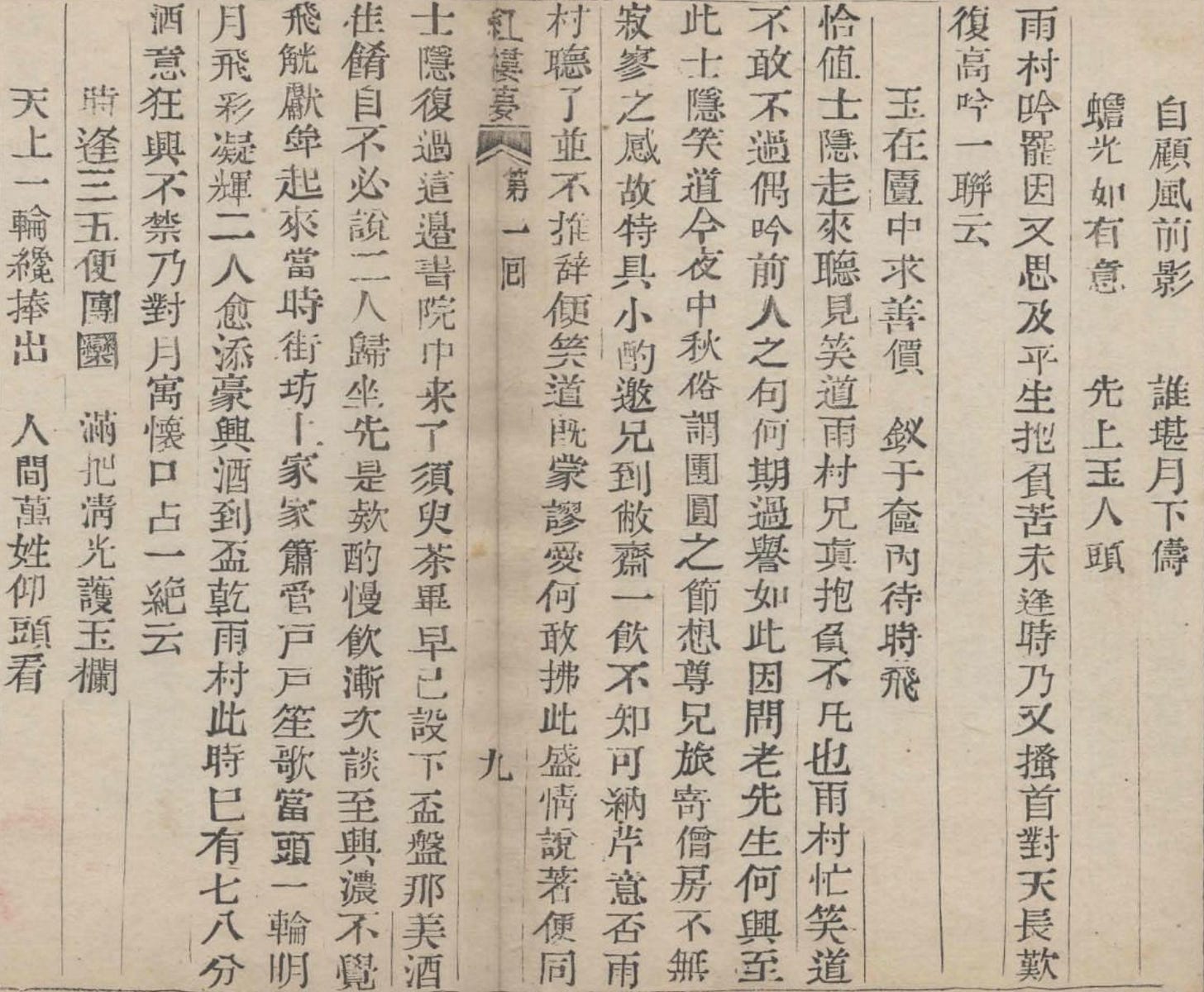

Chinese Text

一時,小童進來。雨村打聽得前面留飯,不可久待,遂從夾道中自便門出去了。士隱待客既散,知雨村已去,便也不去再邀。

一日,到了中秋佳節,士隱家宴已畢,又另具一席於書房,自己步月至廟中來邀雨村。

原來雨村自那日見了甄家丫鬟,曾回顧他兩次,自謂是個知己,便時刻放在心上。今又正值中秋,不免對月有懷,因而口占五言一律云:

未卜三生願,頻添一段愁。悶來時斂額,行去幾回頭。自顧風前影,誰堪月下儔?蟾光如有意,先上玉人樓。

雨村吟罷,因又思及平生抱負,苦未逢時,乃又搔首對天長嘆,復高吟一聯云:「玉在櫝中求善價,釵於奩內待時飛。」恰值士隱走來聽見,笑道:「雨村兄真抱負不凡也!」雨村忙笑道:「不敢。不過偶吟前人之句,何期過譽如此!」因問:「老先生何興至此?」士隱笑道:「今夜中秋,俗謂『團圓之節』,想尊兄旅寄僧房,不無寂寥之感,故特具小酌,邀兄到敝齋一飲。不知可納芹意否?」雨村聽了,並不推辭,便笑道:「既蒙謬愛,何敢拂此盛情?」說著,便同士隱復過這邊書院中來了。

須臾,茶畢,早已設下杯盤。那美酒佳餚自不必說。二人歸坐,先是款酌慢飲,漸次談至興濃,不覺飛觥獻斝起來。當時街坊上家家簫管,戶戶笙歌,當頭一輪明月,飛彩凝輝,二人愈添豪興,酒到杯乾。雨村此時已有七八分酒意,狂興不禁,乃對月寓懷,口占一絕云:

時逢三五便團圞,滿把清光護玉欄。天上一輪才捧出,人間萬姓仰頭看。

Translation Notes

It might seem confusing that Jia Yucun decides to leave instead of waiting (不可久待,遂從夾道中自便門出去了. This was likely a way for Jia Yucun to help Zhen Shiyin save face. It seems that Zhen Shiyin didn’t mind anyway, since he didn’t send for him to come back.

今又正值中秋, “this night just so happened to be the Mid-Autumn [Festival],” is a reference to the romantic nature of the Mid-Autumn Festival. The festival traditionally includes gazing at the moon and pondering the story of the mythological Houyi gazing at the moon for his goddess wife Chang E, which is part of what Jia Yucun is doing here. The Festival was also traditionally a time for young people to find romantic partners.

五言一律 is also known as 五律. This is a form of classical Chinese poetry with 5 characters per line and 8 lines total. There are also strict tonal pattern rules, which is why this is considered to be a “regulated” type of poetry.

三生 refers to the “three lives” in Buddhist reincarnation cosmology – the past, present, and future lives. It implies a karmic bond that spans multiple lifetimes, and is often used in a romantic context, like it is used here. This is kind of like telling a girl that you loved her before you met her, while implying that you’ll be together in any life that comes after this life. A similar Chinese phrase is 三生石上 (on the stone of three lives), which refers to this kind of predestined love.

儔 means “companion” or “mate.” Yucun is looking for a romantic partner to walk together with him under the moonlight. This is also a reference to the romantic aspects of the Mid-Autumn Festival.

玉人 literally means “jade carver,” but is used figuratively to refer to a beautiful woman. There’s also a bit of foreshadowing here, since the word 玉 (Jade) plays an important part in this novel. Both the names Jia Baoyu (賈寶玉) and Lin Daiyu (林黛玉) contain the character 玉, and the piece of stone both carry with them is also jade (玉). This isn’t direct foreshadowing necessarily, but it does hint at one of the motifs that comes up again and again in Dream of the Red Chamber.

櫝 is a small box, and 奩 is a container for women’s cosmetics or jewelry. Note also that 玉 (jade) in the same line refers clearly to the stone (who is Jia Baoyu), and 釵 (the hairpin) is something we saw way back in the beginning of the book as a reference to women. The hairpin is almost certainly a reference to both Lin Daiyu and Xue Baochai (薛寶釵); in fact, the character 釵 is part of Xue Baochai’s name.

Jia Yucun thinks that he’s talking about himself and the maid: he wants to be recognized as a great scholar and wonderful man, but feels that he is inhibited by the world around him. He imagines that the maid wants to be set free from a life of servitude, and has convinced himself that he’s the only one who can do that for her. What he doesn’t realize, however, is that his poem also reflects one of the chief themes of the novel: Jia Baoyu hoping to prove his worth in a world that misunderstands him, and Lin Daiyu longing to fly away from the societal constraints of the world.

團圓之節 means “Festival of Family Gathering.” When I use the phrase “Festival of Reunion,” it implies a family reunion. Zhen Shiyin is alluding to the fact that Jia Yucun has no family to spend the holiday with.

既蒙謬愛,何敢拂此盛情 is extremely formal language. “Since you have shown me such undeserved kindness, sir, how could I refuse your generous offer?” This shows his desire to impress Zhen Shiyin, something that we’ve seen before as the two of them interact. This small line has a real performative feel to it. Interestingly, Zhen Shiyin’s question to Jia Yucun, “不知可納芹意否?” (or “Might you accept this humble offering?) is also overly humble and very polite. 芹意 here means “celery intention” and is a reference to an ancient story about a peasant offering wild celery to a noble man. It symbolizes a modest but sincere gift.

須臾 means “in a short while” or “in an instant,” and is common to see in literary Chinese to convey a fluid transition between scenes.

款酌慢飲 is to sip lightly and drink slowly, and conveys a Confucian ideal of moderation – one that they’re about to break.

飛彩凝輝 literally means “flying goblets and offered cups,” and describes a rowdy drinking scene.

家家簫管,戶戶笙歌 literally means “every household had flutes and pipes; every door had mouth organs and songs.” 簫 and 管 were two kinds of wind instruments; 笙 is a mouth organ, and 歌 is a song. This describes the festive atmosphere around them during the evening of the Mid-Autumn Festival.

飛彩凝輝 describes the radiant and almost magical glow that comes from the moon. 飛彩 means “flying colors,” and 凝輝 means “condensed brilliance.” 凝 is very powerful here, suggesting that the light of the moon has become a tangible object – as if it were liquid light or frozen light.

三五 refers to the 15th day (three times five is 15), which is the date of the Mid-Autumn Festival in the Lunar Calendar.

天上一輪 (a disk in heaven) is clearly a metaphor that Jia Yucun is using for himself. The same is true of the “jade railing” (玉欄) that the moonlight protects. Notice that he once again refers to himself as 玉. This demonstrates Yucun’s ambitions and desires. He’s completely forgotten the maid by now.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

Hawkes continues to undertranslate 知己 here: the maid “convinced [Yucun] that she was a friend.” “Friend” is an understatement when you’re busy composing poems for the girl.

We’ll cover Hawkes’ translation of the three poems presented here tomorrow. His translation mixes interpretation of the poems with a literal translation of the characters (for example, “Ere on ambition’s path my feet are set”).

Hawkes also interprets the line 釵於奩內待時飛 as a direct reference to the Chinese imperial examinations, going as far as to insert a footnote (something that he rarely does throughout the entire novel). Hakwes’ footnote refers to the legend of the divine hairpin (神釵典故), a Tang dynasty story about a lady whose hairpin transformed into a swallow and flew away, symbolizing her ascent to immortality. In connection with this, scholars would hope to fly up to office the way her hairpin flew away. Hawkes is actually likely correct with this interpretation, though he neglects to mention the slightly deeper meaning, in which the hairpin (釵) symbolizes the maid. Again, if Hawkes had bothered to translate the entire first paragraph of the novel, he would have likely seen this connection.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dream of the Red Chamber to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.