Disaster Strikes

For the first time in Dream of the Red Chamber, we have some action. After Jia Baoyu leaves Zhen Shiyin to try to obtain a living in government service, Yinglian disappears. For the first time in this book, we see a tragedy take place.

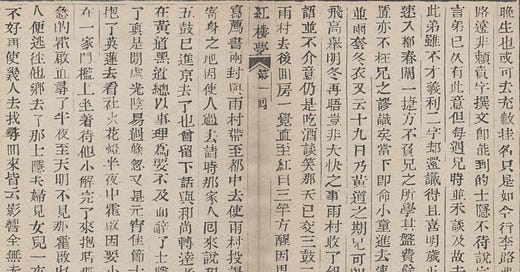

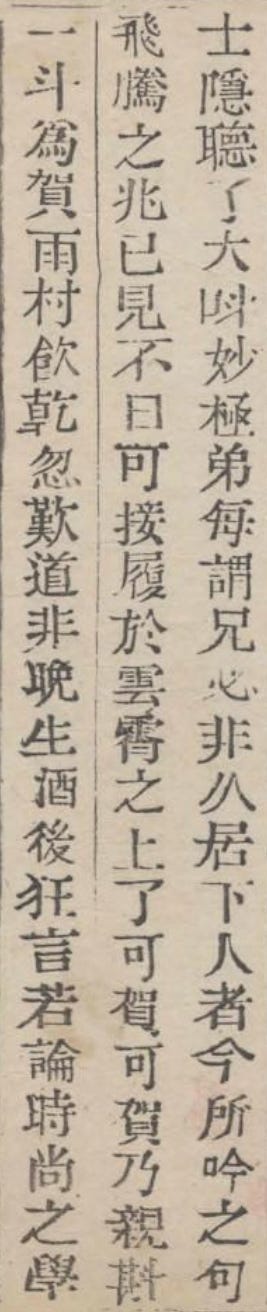

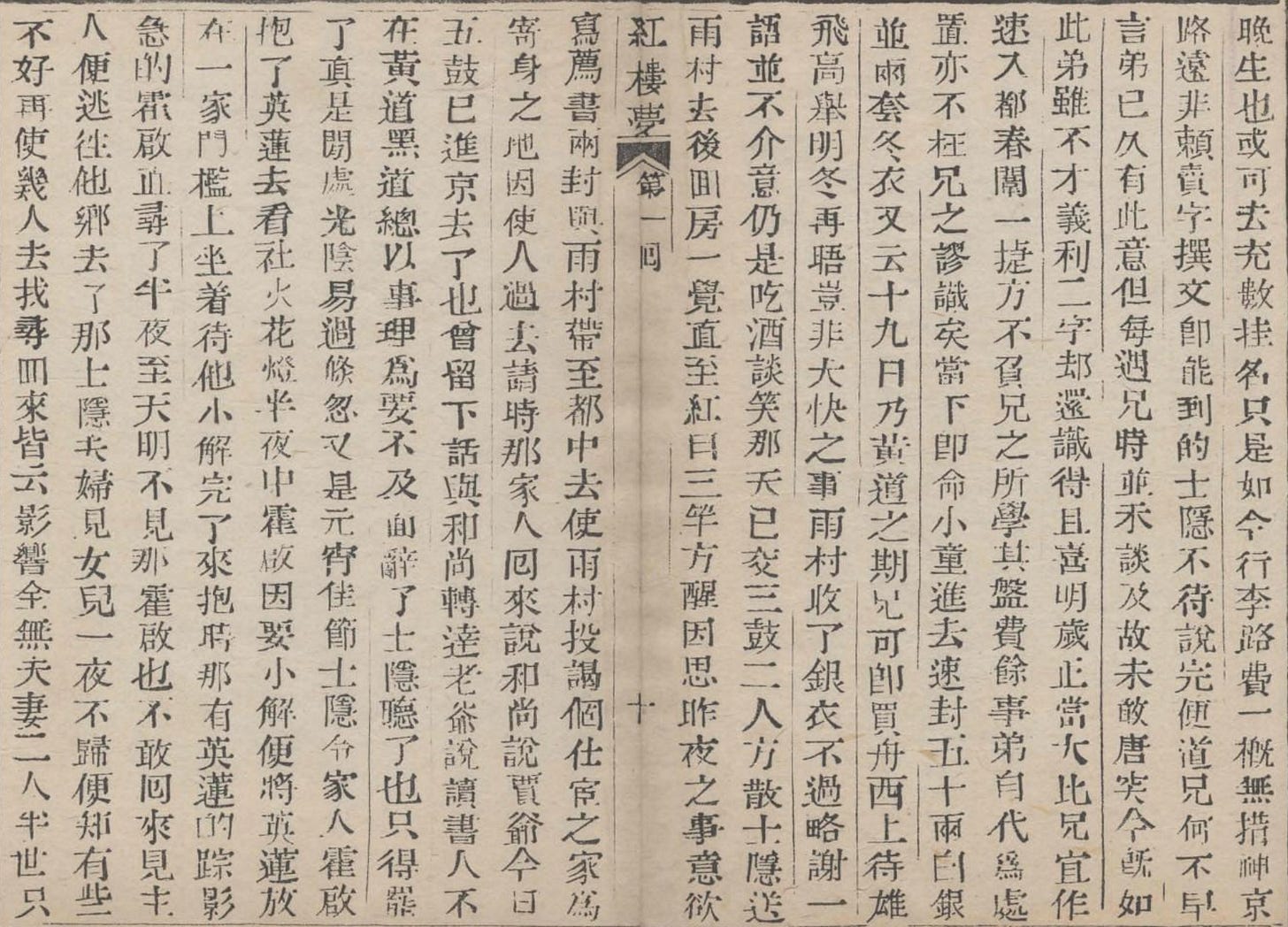

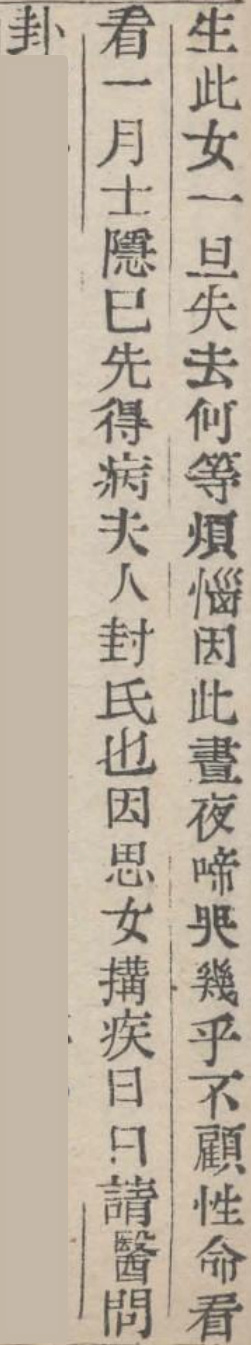

Chinese Text

士隱聽了大叫:「妙極!弟每謂兄必非久居人下者,今所吟之句,飛騰之兆已見,不日可接履於雲霄之上了。可賀,可賀!」乃親斟一斗為賀。雨村飲乾,忽嘆道:「非晚生酒後狂言,若論時尚之學,晚生也或可去充數掛名。只是如今行李路費,一概無措,神京路遠,非賴賣字撰文即能到的!」士隱不待說完,便道:「兄何不早言?弟已久有此意,但每遇兄時,並未談及,故未敢唐突。今既如此,弟雖不才,義利二字卻還識得。且喜明歲正當大比,兄宜作速入都。春闈一捷,方不負兄之所學。其盤費餘事,弟自代為處置,亦不枉兄之謬識矣。」當下即命小童進去速封五十兩白銀並兩套冬衣。又云:「十九日乃黃道之期,兄可即買舟西上。待雄飛高舉,明冬再晤,豈非大快之事?」雨村收了銀衣,不過略謝一語,並不介意,仍是吃酒談笑。那天已交三鼓,二人方散。

士隱送雨村去後,回房一覺,直至紅日三竿方醒。因思昨夜之事,意欲寫薦書兩封與雨村帶至都中去,使雨村投謁個仕宦之家為寄身之地,因使人過去請時,那家人回來說:「和尚說,賈爺今日五鼓已進京去了,也曾留下話與和尚轉達老爺,說:『讀書人不在黃道黑道,總以事理為要,不及面辭了。』」士隱聽了,也只得罷了。

真是閒處光陰易過,倏忽又是元宵佳節。士隱令家人霍啟抱了英蓮去看社火花燈。半夜中,霍啟因要小解,便將英蓮放在一家門坎上坐著。待他小解完了來抱時,那有英蓮的蹤影?急的霍啟直尋了半夜,至天明不見,那霍啟也不敢回來見主人,便逃往他鄉去了。

那士隱夫婦見女兒一夜不歸,便知有些不好,再使幾個人去找尋,回來皆云音訊全無。夫妻二人,半世只生此女,一旦失去,何等煩惱!因此,晝夜啼哭,幾乎不顧性命。看看一月,士隱已先得病;夫人封氏,也因思女遘疾,日日請醫問卦。

Translation Notes

弟每謂兄, “I’ve always said that you, my brother,” is a humble expression on the part of Zhen Shiyin. He calls himself 弟, younger brother, though it’s clear that he is older than Jia Yucun – who he refers to as 兄, older brother.

親斟 means “he poured [the wine] himself,” which emphasizes Shiyin’s respect for Yucun.

時尚之學 (today’s fashionable learning) probably refers to the so-called “eight legged essay” (八股文), which was the type of formal and uncreative writing required to pass the imperial exams. Note that there is a hint of scorn in this statement, as if Jia Yucun were somehow above the “learning of the day.”

充數掛名 is similar. It literally means “to fill a quota in name only,” which suggests a perfunctory or token role. Yucun is saying something here like, “when it comes to the way they study these days, I could probably just barely skate by.” Again, there is a very clear hint of pride and confidence in his own ability couched in what is otherwise humble language.

唐突 means to be rude, blunt, offensive, or presumptuous. “Presume” here fits best.

大比 refers to the imperial examinations, and was a colloquial term referring to the examination system in general. The examinations had four general stages:

The “entry-level” examinations (童試), which were held every year and were available to students as soon as they were in their early teens;

The provincial examinations (鄉試), which were held once every three years in provincial capitals;

The metropolitan examinations (會試), which was held once every three years in the nation’s capital, and was usually held a year after the 鄉試; and

The palace examination (殿試), which was usually held immediately after the 會試.

If you’re really curious, you can learn a whole ton on the Wikipedia page for the Chinese imperial examinations.

When Zhen Shiyin tells Jia Yucun that he needs to prepare for the 大比, what he means is that it’s time for the provincial examinations. Jia Yucun would have passed the “entry-level” examinations years before. It’s important that Yucun hurries, of course, because his next change won’t be until three years from now.

春闈 refers to the metropolitan examinations. 春 means “spring,” and those examinations were typically held in April. 闈 is a word for the imperial examination hall or room.

不枉 means “not in vain,” and 謬 means “false.” When Zhen Shiyin says 亦不枉兄之謬識矣, what he’s saying is something like “the misguided friendship you have with me will not be in vain.”

兩 is a tael, a traditional method of weight. It’s short for 市兩, which was one tenth of a 市斤. A tael was basically 50 grams. Wikipedia has more information on how this currency measure worked.

黃道之期 means “an auspicious date.” 黃道 literally refers to the “ecliptic,” or the path that it seems the sun takes along the celestial sphere when viewed from the earth. In this context, 黃道 refers to certain aligning of the stars that meant there would likely be good luck. 黃道吉日 is another idiom that refers to the same “auspicious date” concept.

三鼓 refers to the third “night watch,” which was around 11 PM to 1 AM. Meanwhile, 紅日三竿 meant the late morning: literally “the sun was three poles high,” referring to about 9 to 11 AM. This refers to the “geng-dian system” of timekeeping, which you can read about on Wikipedia in further detail. Basically, time at night was divided into six “更” marked by a signal given by a gong or a drum. Here, Cao Xueqin uses the word 鼓, “drum,” to refer specifically to the time that the drum was hit. In contrast, the system Cao Xueqin refers to that was used to keep time during the day involved a vertical pole (表) being placed on a sundial platform (圭), where the time was measured by the length of the shadow of the pole, indicated by 竿. 三竿 would therefore mean that the sun had risen enough to cast shadows that were about 3 times the pole’s height.

When Yucun passes along the “不及面辭” message, he’s not only breaching etiquette. He’s snubbing Zhen Shiyin outright. Or, like The Eagles once sung, he’s taking the money and running.

閒 means “a place of leisure” or “idleness.”

The name 霍啟 (Huo Qi) is a homophone with 禍起, or “disaster arises.”

小解 means to urinate.

門坎, or 門檻, means the doorstep or the threshold of a door. Here the 門坎 is also symbolic, as it represents the transition Yinglian takes from one world to another.

那有 here would most likely be written as 哪有 today. As Wiktionary correctly states, the character 哪 (where, as opposed to 那, which means “over there”) did not exist in Chinese before the 20th century. Interestingly enough, modern versions of 紅樓夢 from both Taiwan and China use 那 in this instance instead of the more modern version. It keeps you on your toes when you read.

問卦 refers to divination – a desperate attempt to do something to find their daughter. Notice in particular that they do not use other possible methods to locate her, such as contacting the authorities. There wasn’t much of a police force in those days to help them, and that’s part of the point: Cao Xueqin is showing here that this was one of the many tragedies of the time that unfolded in silence, with little public attention.

Translation Critique

Hawkes

Hawkes translates 大比 as “the Triennial,” which must be extremely confusing to any English reader of his translation. This is the problem with trying to find a single word in English to match the meaning of a single word in Chinese. Sometimes it’s better to use notes to explain things.

For 讀書人不在黃道黑道,總以事理為要,不及面辭了, Hawkes writes “A scholar should not concern himself with almanacs, but should act as the situation demands.” The translation is fine, I suppose, but the reference to “almanacs” is a pretty obscure one in English usage. Most people who remember the days of printed almanacs would think of them as an encyclopedic single volume history work focusing on the most recently finished year, not necessarily as some sort of superstitious means of divination.

霍啟 is named Calamity in Hawkes’ translation. It’s the first of many examples we’ll see of Hawkes translating ordinary character names according to the hidden homophonic meanings. I don’t care much for this practice, and will continue to refer to characters by their Chinese names, complete with notes.

Yang

The Yangs note only that “every day they sent for doctors” at the end, missing the superstitious (and desperate) weight of 問卦 (asking questions through divination).

My Translation

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dream of the Red Chamber to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.